Characters:

Characters:

Three Cherokee Conjurors

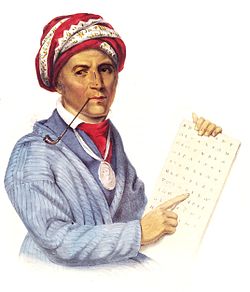

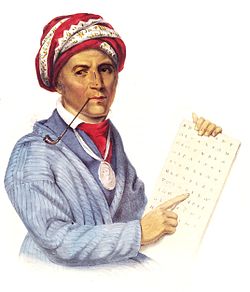

Sequoyah

The scene is a forest clearing near the Cherokee town of Willstown, Alabama, in 1821. Sequoyah stands facing three conjurors, a leather bag hanging from his shoulder.

1ST CONJUROR. George Guess, do you know why we have summoned you?

SEQUOYAH. So I may plead for my life. But I don’t know why. You’ve already decided to kill me.

1ST CONJUROR. It’s said that you’re possessed by an evil spirit.

SEQUOYAH. A shee-leh.

2ND CONJUROR. Yes.

SEQUOYAH. And the only way to destroy a shee-leh is to kill the creature it possesses. Go on and do it, then.

2ND CONJUROR. But is it true?

3RD CONJUROR. Are you possessed?

SEQUOYAH. Wouldn’t I be the last to know?

1ST CONJUROR. Tell us.

SEQUOYAH. So I must plead for my life, or you’ll bore me to death. Wait just a moment …

(SEQUOYAH reaches into his bag, takes out a small wooden board, a few pieces of paper, and a pencil. He squats on the ground, puts the board on his knees as a makeshift desk with paper on top of it, then takes the pencil in hand.)

SEQUOYAH. I’m ready.

3RD CONJUROR. What are those things?

SEQUOYAH. This is paper, of course. But here’s something new, even to me. A pencil, white men call it. Like a pen, except it doesn’t use ink. Yesterday I bought a dozen of them from a passing white peddler. A fine tool. Have a look.

(SEQUOYAH holds the pencil toward the CONJURORS, who draw back fearfully.)

SEQUOYAH. It won’t bite. Just a little wooden rod with a core of hard black stuff—graphite, it’s called. When it’s whittled to a point, the graphite leaves lines—like ink, only dry. While I’m weeping and groveling, I don’t want to keep dipping a quill in an inkwell.

(SEQUOYAH begins to write.)

1ST CONJUROR. What are you doing?

SEQUOYAH. Writing down what we say.

2ND CONJUROR. So you use your magic right in front of us!

3RD CONJUROR. The magic of talking leaves!

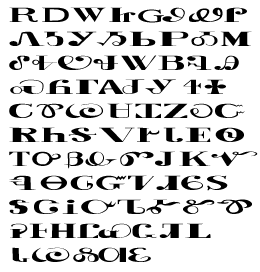

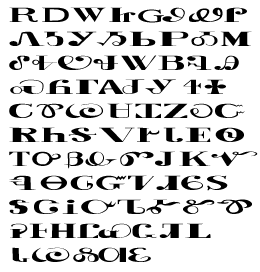

SEQUOYAH. It’s not magic. I learned how to do it on my own. I listened to the sounds of our speech, then made up marks for them.

1ST CONJUROR. White men make marks like yours. They’re evil magic.

SEQUOYAH (writing furiously). Could you talk more slowly?

1ST CONJUROR. We’ll talk as fast as we like.

SEQUOYAH. Well, then. I won’t try to write everything.

(SEQUOYAH writes more slowly, and only intermittently.)

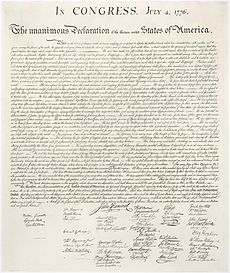

SEQUOYAH. Talking leaves give the white man power. He can put his thoughts on paper, then send those thoughts to a friend far away—over hills, plains, and rivers. Then that friend can reply with leaves of his own. Talking leaves destroy distance—that great, invisible shee-leh that thwarts us all. Without talking leaves, the white man could never subdue us. They are his most powerful tool.

3RD CONJUROR. His tool, not ours.

1ST CONJUROR. His way, not ours.

SEQUOYAH. How odd. I sit here accused of practicing his magic while neglecting my cattle and hogs, my plow and manure. But farming is the white man’s way. He forced it upon us to stop us from hunting and roaming. If I tear up my magic leaves, will you burn down your barns, kill your livestock, salt your fields? And what about horses, which I’m told the white man brought here ages ago?

1ST CONJUROR. Horses have always been ours. The Great Spirit gave them to us.

SEQUOYAH. Well, so you say. What about rifles? Each of them is stamped with the name of the white man who made it. Give yours to me, and I’ll melt them down in my forge, make lumps of iron out of them, put them back in the hills where they belong. Oh, but I forgot—blacksmithing is also the white man’s way. I must destroy my forge. To become pure Cherokee again, we must reject all the white man’s ways—even those we need to defend ourselves against him.

(Pause)

3RD CONJUROR. Tell us, George Guess—do you know why talking leaves belong to the white man and not to us?

SEQUOYAH. I’ve never heard the story.

1ST CONJUROR. In the beginning, the Great Spirit created us real people, and then he created the white men. Because we came first, he gave us a great gift—books with talking leaves that would grant our every wish. To the white men, he gave a lesser gift—the bow and arrow. But we Indians never bothered to use our books. They lay gathering dust. At last, the white men crept along and snatched them away, leaving bows and arrows in their place. Since then, we have lived short, hard lives pursuing and killing creatures of the wild, while the talking leaves have blessed the white men, giving them command of all creation. The Great Spirit has never forgiven our neglect and thanklessness. Few are the blessings he has granted us.

(SEQUOYAH laughs.)

1ST CONJUROR. You find it funny?

SEQUOYAH. Yes, because I know the real truth. The moon laughs—laughs loudly, day and night.

2ND CONJUROR. I’ve never heard the moon laugh.

SEQUOYAH. Neither have I. But the white man does hear it—and the Great Spirit blesses him for that.

3RD CONJUROR. This story is a lie.

SEQUOYAH. But it was told to me by my mother—Wurteh, sister of Old Tassel.

2ND CONJUROR. The sister of Old Tassel could never lie.

SEQUOYAH. Ah, but mightn’t I lie—say that my mother told me a story when she didn’t? And how can I know that your story isn’t a lie? How can we Cherokee ever know what’s truth or lie, fact or imagination? The white man knows. His talking leaves tell him.

(SEQUOYAH shows them a piece of paper.)

SEQUOYAH. Imagine that my mother had written the story of the laughing moon on this paper, many years ago. Imagine that she swore to its truth by making a mark right here—a mark that was hers alone. Would you believe it then?

1ST CONJUROR. Yes.

SEQUOYAH. Then you grasp the greatest gift of the talking leaves—the gift of memory. The white man knows who he is, remembers all he has done, possesses a power he calls history. We Cherokee scarcely remember our grandfathers. And though our heads are full of old stories, how can we be sure that we recall those stories aright? Have we changed them in telling and retelling them again and again?

3RD CONJUROR. We trust the Great Spirit to preserve the truth of our stories.

SEQUOYAH. Yes, and it’s your job to keep telling them. But look at yourselves. You’re old and near death. How many young men stand trained and ready to carry on your work? None. The missionaries have converted them all to the white man’s religion. This way of writing I’ve made—it’s all that stands between you and forgetfulness. Your spells, your charms, your medicines, your wonder-working dances and songs—all will be lost without magic leaves.

(Silence)

SEQUOYAH. You don’t care, then? I see you’ve accepted the white man’s religion after all.

1ST CONJUROR. We’ll never do that.

SEQUOYAH. Oh, but you have. You love your enemies, bless those who curse you. And if a man steals your coat, you give him your pants and shoes and hat as well. And if he hits you on one side of the head, you turn so he can hit you on the other side. And most of all, you always do for others what you wish they would do for you. And why should I blame you? Those are good ways, blessed ways. After all, the missionaries teach that the meek shall inherit the earth.

2ND CONJUROR. The meek inherit nothing.

3RD CONJUROR. The white man overruns the earth by force.

SEQUOYAH. That’s the clever wickedness of his religion. Its lessons are meant to be disobeyed. When their chief spirit came among them, the first thing the white men did was kill him. They fastened him to a tree with iron barbs made in their forges, riddled him with spears, tormented him with thorns, until at last he died of pain. When he returned from the dead, he blessed his murderers for their cruelty—and that’s been the secret of the white man’s religion ever since. When they disobey their spirit, he blesses them; when they obey him, he curses them. Always do what the spirit says not to do—that’s the white man’s creed. Disobedience is the only path to Christian salvation. But every day, the missionaries teach our children to obey this religion of disobedience, making them fit for slaughter. Our only weapon against this evil is the talking leaves.

(Silence)

SEQUOYAH. And I’ll show you how to use them. Do you wish it?

(Silence)

SEQUOYAH. Well. Stop calling me by the name I got from my white father. Call me by the one my mother gave me. I’ll write it for you sound by sound. Look.

(The CONJURORS huddle around SEQUOYAH, watching as he writes.)

SEQUOYAH. Se … quo … yah.

END OF PLAY