When I wrote my award-winning play The Shackles of Liberty, Donald Trump had not yet risen to power. Even so, I can’t help thinking my play has some relevance to our situation today. What does it mean that America’s cherished ideals of democracy and liberty are under threat by people who profess those very ideals?

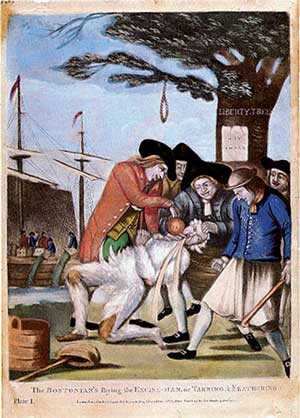

Colonists gathered around the Liberty Tree in Boston, Massachusetts.

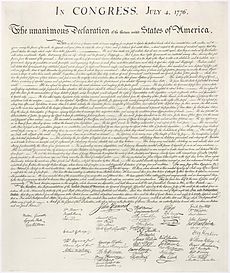

Thomas Jefferson famously wrote of a “tree of liberty” that “must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots & tyrants.” In The Shackles of Liberty, my fictional Jefferson elaborates on this image …

But the branches—how like a multi-headed monster, a vicious hydra with all of its faces at war, one against the other, the terrible faces of Liberty.

These words may sound incongruous coming from the lips of America’s most eloquent (if hypocritical) advocate of liberty. But my Jefferson is reflecting on the central contradiction of his own life—that his own liberty was built upon the enslavement of others. He’s also contemplating a lurking contradiction in the very idea of freedom …

“Freedom for the pike is death for the minnows.”

Isaiah Berlin (Rob C. Croes).

This old saying was a favorite of the late philosopher Isaiah Berlin. In his 1958 essay “Two Concepts of Liberty,” Berlin explores the distinction between negative and positive liberty. Negative liberty is essentially liberty from, the freedom to live one’s life without interference. Positive liberty is liberty to, the freedom of self-determination. As Berlin puts it …

The “positive” sense of the word “liberty” derives from the wish on the part of the individual to be his own master.

When Jefferson wrote of our “inalienable” right to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” it seems to me that he was arguing for liberty in the positive sense. So was Patrick Henry when he demanded in 1775, “give me liberty or give me death!” I think that positive liberty lies at the very core of American aspiration and purpose. It has been a key to progress in America’s great moral struggles, including the abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, and LGBTQ rights.

But like all noble ideals, positive liberty can be dangerous. In a society based on the assumption “that all men are created equal,” every individual expects to share an equal right to “the pursuit of Happiness,” and an equal participatory role in the political process that guarantees this right. And as Queen Elizabeth tells William Shakespeare in my short play The Throne and the Mirror …

The tyranny of the one is not worth fearing; the tyranny of the many, of the all—now that’s a tyranny to terrify any sane soul.

A customs commissioner is tarred and feathered by the Sons of Liberty under the Liberty Tree in Boston. Tea is being poured into his mouth; the Boston Tea Party is seen taking place in the background.

Our founders, including James Madison, John Adams, and Alexander Hamilton warned against this very danger—“the tyranny of the majority.” Majority rule is hardly a guarantee against injustice, especially when the majority chooses to serve its own pettiest interests and fails to consider what is just for all. American slavery and European fascism were both consequences of majority will turned to evil.

Such a perversion of democracy has given us Donald Trump, a manifestly narcissistic and incompetent would-be dictator. The majority of Americans are still not sufficiently horrified by the threat he poses to our republic to remove him from office by constitutional means. We are in a true crisis of democracy, in the grip of a doctrine that Trump and his followers regard as heroic and unassailable.

This doctrine holds that traditions surrounding the American flag and the national anthem should be enforced as mandatory expressions of patriotism; that most immigrants come to this country with malicious purpose; that the news media is a purveyor of “fake news,” an “enemy of the people” that ought to be muzzled; and many other specious and ugly ideas, all of them touted in the names of America’s highest ideals, including democracy and liberty.

Tragically, Trump’s followers fail to perceive the ruin this doctrine is bringing upon themselves. As Berlin puts it …

The triumph of despotism is to force the slaves to declare themselves free. It may need no force; the slaves may proclaim their freedom quite sincerely: but they are none the less slaves.

But what can be done to defeat Trumpism? The upcoming midterm elections are, of course, vitally important; but the problem won’t be solved even if Trump’s congressional sycophants are thrown out of office, or if Trump himself is deposed in 2020 or even before. The spirit of Trumpism will endure, at least for a time, impervious to truth, the rule of law, and the tears of frightened children locked in cages.

Henry David Thoreau, 1856.

Indeed, Henry David Thoreau argues in “Civil Disobedience” that voting is but a feeble weapon against injustice …

I cast my vote, perchance, as I think right; but I am not vitally concerned that that right should prevail. I am willing to leave it to the majority. Its obligation, therefore, never exceeds that of expediency. Even voting for the right is doing nothing for it. It is only expressing to men feebly your desire that it should prevail. A wise man will not leave the right to the mercy of chance, nor wish it to prevail through the power of the majority.

So what is to be done? I wish I knew. But I’m fairly sure that the abusers of positive liberty now in power can only be defeated by conscientious and decent people exercising their own positive liberty—and doing so with the fullest possible energy and goodwill.

In my play, Thomas Jefferson asks about those “terrible faces of liberty” …

Why can’t they see that the sky is filled with sunlight, that there is Freedom in infinite abundance, and Happiness bountiful enough for every creature that lives or ever shall—not merely to share but to give, one unto another, until the sun exhausts its perpetual light?

It’s an impossible ideal, of course—and Isaiah Berlin warns against the potential evil of impossible ideals. But if we keep striving toward greater and greater heights of acceptance, inclusion, generosity, equality, and love, I can’t help thinking our current evils will recede; our wounded republic may even begin its long healing.

The text of The Shackles of Liberty is available on the New Play Exchange or by contacting Wim personally.