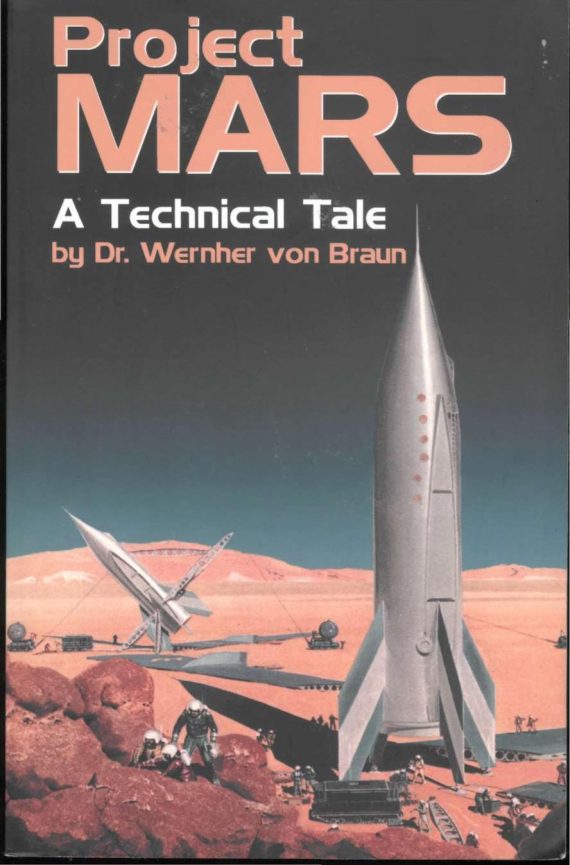

Characters:

Adolf Hitler

Wernher von Braun

The scene is Adolf Hitler’s vast office in the New Reich Chancellery in Berlin, December 1944. Downstage, an imaginary window in the “fourth wall” looks out into the night. Hitler is seated at his desk. Wearing an SS uniform, Wernher von Braun enters and salutes.

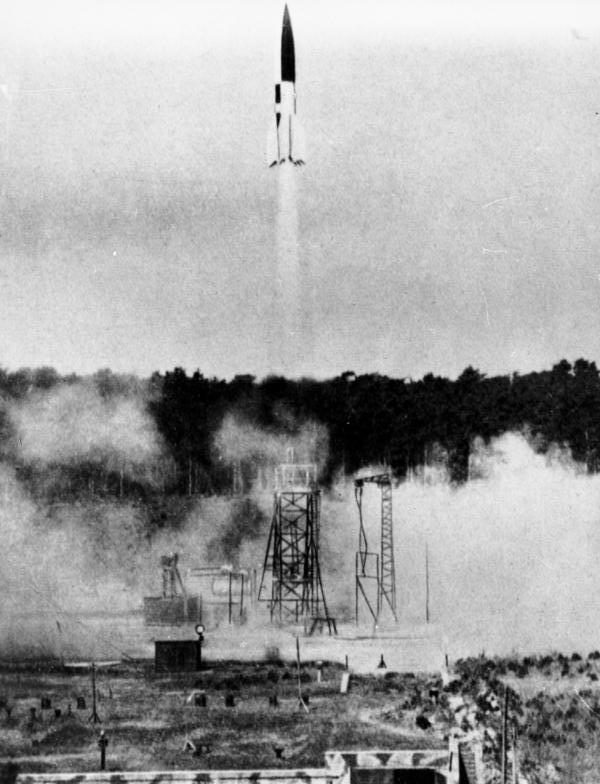

V-2 launch in 1943.

VON BRAUN. Sieg Heil, Mein Führer!

(HITLER rises from his chair and begins stalking around VON BRAUN, who stands at attention.)

HITLER. Major von Braun, where are my rockets?

VON BRAUN. Sir?

HITLER. My Vengeance Weapons. Where are they?

VON BRAUN. Mein Führer, I don’t understand.

HITLER. It is a simple question, Major von Braun.

VON BRAUN. You have your V-2 rockets, Mein Führer. Several thousands of them.

HITLER. Several thousands.

VON BRAUN. Yes, Mein Führer. They’re being launched daily from mobile sites in western Holland.

HITLER. Several thousands.

Damage caused by a V-2 rocket attack in Whitechapel, London.

VON BRAUN. Raining death upon London, sir.

HITLER. Why have you disobeyed my orders?

VON BRAUN. Mein Führer?

HITLER. Some three years ago, when you showed me plans for the V-2, I ordered the production of hundreds of thousands. Enough to turn all of London into a lake of flame, fire and fury like the world has never seen. You promised exactly that. Raining death, you say? Your rain is but a puny drizzle. Where are my rockets?

VON BRAUN. Sir, we couldn’t reckon on …

HITLER. On what?

VON BRAUN. Sir, the laborers can’t —

HITLER. You have all the forced labor you could possibly need from Mittelbau-Dora.

VON BRAUN. Yes, but slave laborers have an unfortunate way of …

VON BRAUN. Yes, but slave laborers have an unfortunate way of …

HITLER. Of what?

VON BRAUN. Dying.

HITLER. How?

VON BRAUN. Overwork. Starvation. Disease. What have you. Sir.

HITLER. So I hear. More laborers die making the rockets than Londoners die from their warheads! Take more slaves from Mittelbau-Dora. Empty the camp if need be. Then take more from Buchenwald. The supply will be endless, I promise you. You’ll have millions to choose from.

VON BRAUN. Yes, sir. But there is also the matter of raw materials, sir.

HITLER. Materials! Always materials! Are you telling me that hundreds of thousands of rockets are an impossible task?

VON BRAUN. So it would seem, sir.

HITLER. Why did you not reckon this three years ago?

VON BRAUN. A terrible miscalculation, sir.

(Pause)

HITLER. You may relax, Major von Braun.

(VON BRAUN stands at ease, but anything but relaxed; there is no place for him to sit.)

HITLER. You were jailed in Stettin last March, were you not?

VON BRAUN. Regretfully, yes, Mein Führer.

HITLER. Do you know why?

VON BRAUN. I was never entirely clear about that, Mein Führer.

HITLER. You were suspected of sabotaging your own rocket program. You were also suspected of planning an escape from the Reich. A truly astonishing escape. Not to England, or America, or Russia—but to the planet Mars!

VON BRAUN. Sir, I assure you that I never planned any such —

HITLER. Do you know why I’ve summoned you?

VON BRAUN. I received your memo, Mein Führer.

HITLER. And what did you glean from my memo?

VON BRAUN. You want to speak to me about Operation Ares.

HITLER. And what are your thoughts on Operation Ares?

VON BRAUN. Regretfully, I have no thoughts on Operation Ares.

HITLER. And why not?

VON BRAUN. Because, Mein Führer, I have never heard of Operation Ares.

(Pause)

HITLER. You’ve also been overheard making defeatist remarks about the war.

VON BRAUN. If so, my words have been terribly misunderstood.

HITLER. No? You haven’t been repeating vicious lies? That the Reich is crumbling? That the war effort is failing? That the Allies have taken back France? That the Russians are advancing upon us from the east?

VON BRAUN. I’ve said no such things, Mein Führer.

HITLER. But you’ve heard such lies?

VON BRAUN. I give them no credence, Mein Führer.

HITLER. Before you leave this office, I demand a list of every voice you’ve heard spreading such lies.

VON BRAUN. Yes, Mein Führer.

HITLER. I am about to launch an offensive in the forest of the Ardennes, crushing the Allied armies underfoot. The Russians, too, will live to regret their encroachment upon our realms. The Reich has never been so close to victory, believe me.

VON BRAUN. I have complete faith in the destiny of Reich, Mein Führer.

(Pause)

HITLER. Do you deny that you want to go to Mars?

HITLER. Do you deny that you want to go to Mars?

VON BRAUN. I never intended to escape —

HITLER. Do you want to go to Mars?

VON BRAUN. Yes, sir, I do. Very much, sir.

HITLER. Is it possible to go to Mars?

VON BRAUN. I believe it is entirely possible, sir.

HITLER. Explain.

VON BRAUN. I have in mind a fleet of ten spaceships carrying a total of seventy men. The voyage, if optimally timed, should take thirteen months and six days.

HITLER. Why aren’t we building such spaceships right now?

VON BRAUN. We will if you command it, Mein Führer.

HITLER. And how do you suppose we shall be greeted by the Martians?

VON BRAUN. Sir?

HITLER. The natives. The inhabitants. Will they greet us as friends, liberators, enemies?

VON BRAUN. Mein Führer, it is by no means certain that there is any life at all —

HITLER. There is intelligent life on Mars. My people tell me so.

VON BRAUN. There might be, sir, but —

HITLER. It is a certainty. I have it on good authority.

(HITLER goes to his desk and unrolls a large map.)

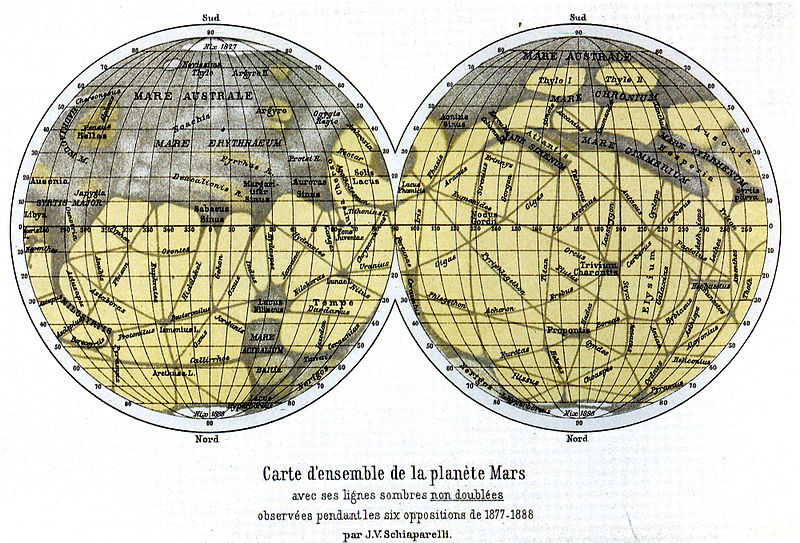

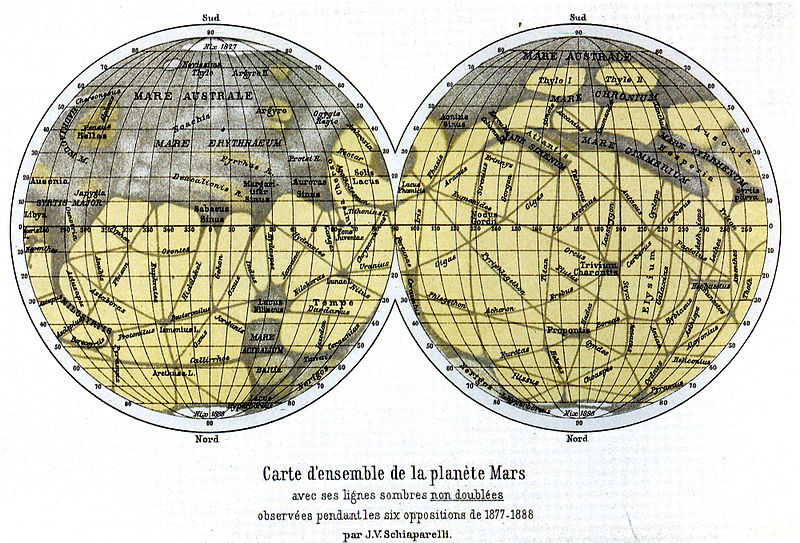

1888 map of Mars by Giovanni Schiaparelli.

HITLER. I have here a detailed map of Mars and its canals—a vast and sophisticated network, a miracle of engineering that could only have been built by an extremely advanced civilization.

VON BRAUN. Sir, I am familiar with that theory, and I must regretfully say —

HITLER. That all this is impossible?

VON BRAUN. Not impossible at all, but —

HITLER. Surely you will not tell me that this map is in any way false or inaccurate.

VON BRAUN. It is a very old notion, sir, and more recent observations —

HITLER. I received it from the Reich’s most brilliant astronomers.

VON BRAUN. Very well, sir.

HITLER. So let me ask again—how will we be greeted by the Martians?

VON BRAUN. I haven’t the slightest idea, Mein Führer.

(HITLER rolls up the map.)

HITLER. Major von Braun, I can’t say I’m at all pleased by what I’m hearing. Surely the world’s other great powers have advanced space programs, while the Reich seems to have none at all. What about the Americans?

VON BRAUN. They’ve scarcely given it any thought, sir.

HITLER. The British?

VON BRAUN. Even less, sir.

HITLER. The Russians?

VON BRAUN. The Soviets have far-reaching hopes for space travel.

HITLER. How so?

VON BRAUN. It isn’t easy to … articulate, Mein Führer.

HITLER. What is its guiding spirit?

VON BRAUN. Sir?

HITLER. The fundamental principle, the single thought, the solitary word that sums up the aspirations and the philosophy of the Soviet space program. What is it, Major von Braun?

VON BRAUN. I cannot say.

HITLER. Cannot or will not? Come, come, Major. I’m not squeamish. I’m prepared to hear any notion, however vile or repugnant or obscene, any sort of sick and depraved Judeo-Bolshevist perversion —

VON BRAUN (interrupting fearfully). It’s love, Mein Führer.

(Pause; VON BRAUN clearly dreads HITLER’s reaction to this awful revelation.)

HITLER. Love?

VON BRAUN. Yes, Mein Führer. Love and …

HITLER. Well?

VON BRAUN (with mounting dread). Altruism.

HITLER. Explain.

VON BRAUN. The Russians’ greatest rocket engineer was also a philosopher.

HITLER. His name?

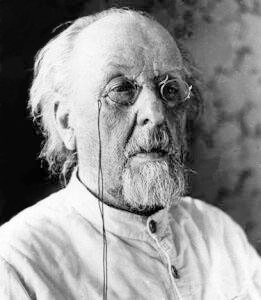

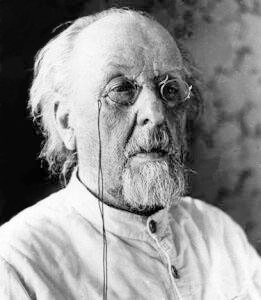

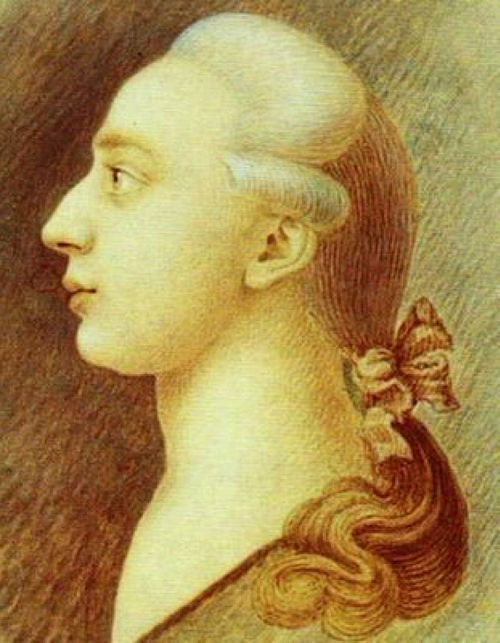

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky

VON BRAUN. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.

HITLER. His beliefs?

VON BRAUN. That Earth is the cradle of humanity, but one cannot live in the cradle forever. That the Cosmos is perfect, and its cause and purpose is nothing else but love. That the universe is inhabited by untold billions of perfect races, and it is the destiny of humankind to join in their perfection; to resurrect the dead and grant them happiness and immortality; to selflessly spread love among the stars, throughout the infinite and the eternal.

HITLER. A loving Cosmos.

VON BRAUN. Yes, Mein Führer.

HITLER (shuddering). Yes, I have sensed this possibility myself.

VON BRAUN. Sir?

(HITLER holds out his hand to VON BRAUN.)

HITLER. Come. Let us look into the night together. Let us talk of Operation Ares.

(VON BRAUN takes his hand; they go downstage and gaze through the imaginary “fourth wall” window into the night.)

HITLER. With every passing night, I believe I see fewer and fewer stars. Some grow dim, some disappear altogether. (pointing) Look, right now, at that one, flickering with its last gasp of light. Last night it was large and blazing. Tomorrow I’ll look for it and it will be gone, just an empty pocket in the sable velvet void. The universe is dying, trudging in the funereal footsteps of its lame and senile God of Love, doomed to share in his wretched extinction. It’s pitiable! The sin of pity creeps up inside of me. But what need has the universe of my pity? It needs rather my fist, my rage, my volcanic cruelty. It begs for conquest, whimpers for a master to teach it strife and destruction, to breathe a fresh conflagration of hatred into its waning orbs. For struggle, not love, is the father of all things—and the more brutal the struggle and the more fierce the hatred, the greater life becomes, and the brighter the heavens. (clenching his fist) I’ll soon crush Russia with the Reich’s great hatred, and Britain, and America. I’ll teach hatred even to my enemies, those who most profess their love. I’ll make our planet great again. And then … Major von Braun, together we must conquer Mars.

VON BRAUN. Yes, Mein Führer.

(HITLER goes to his desk and spreads the map again; VON BRAUN joins him.)

HITLER. Let us prepare for Operation Ares.

END OF PLAY.

—Wim

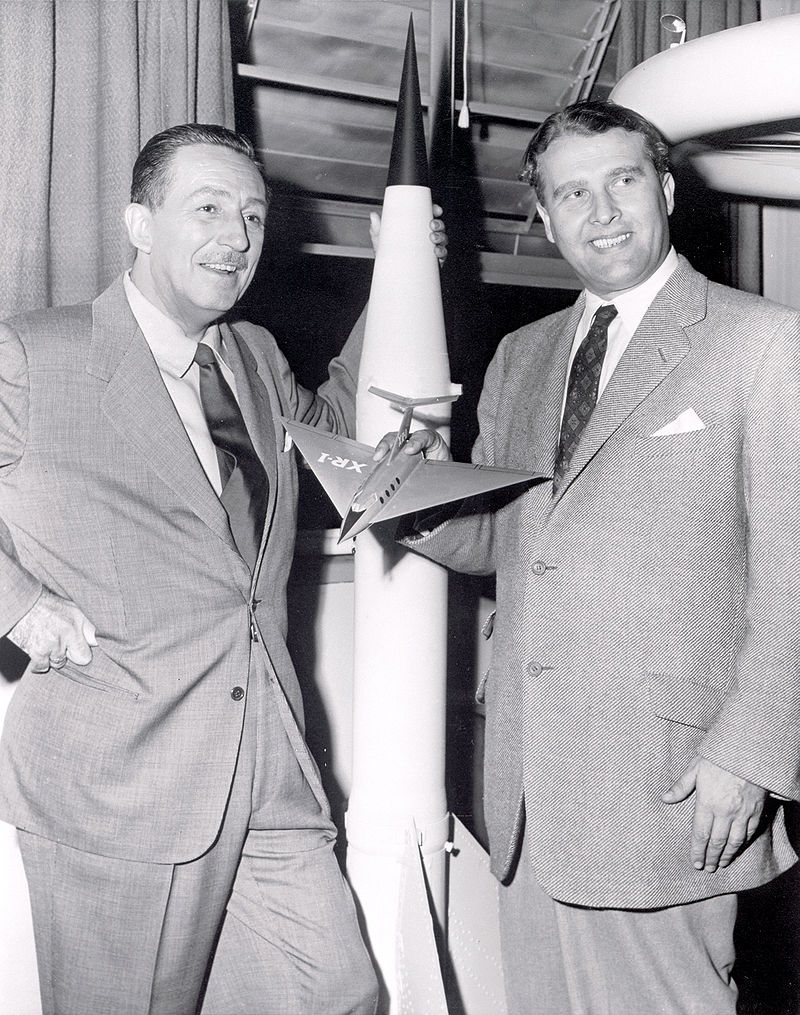

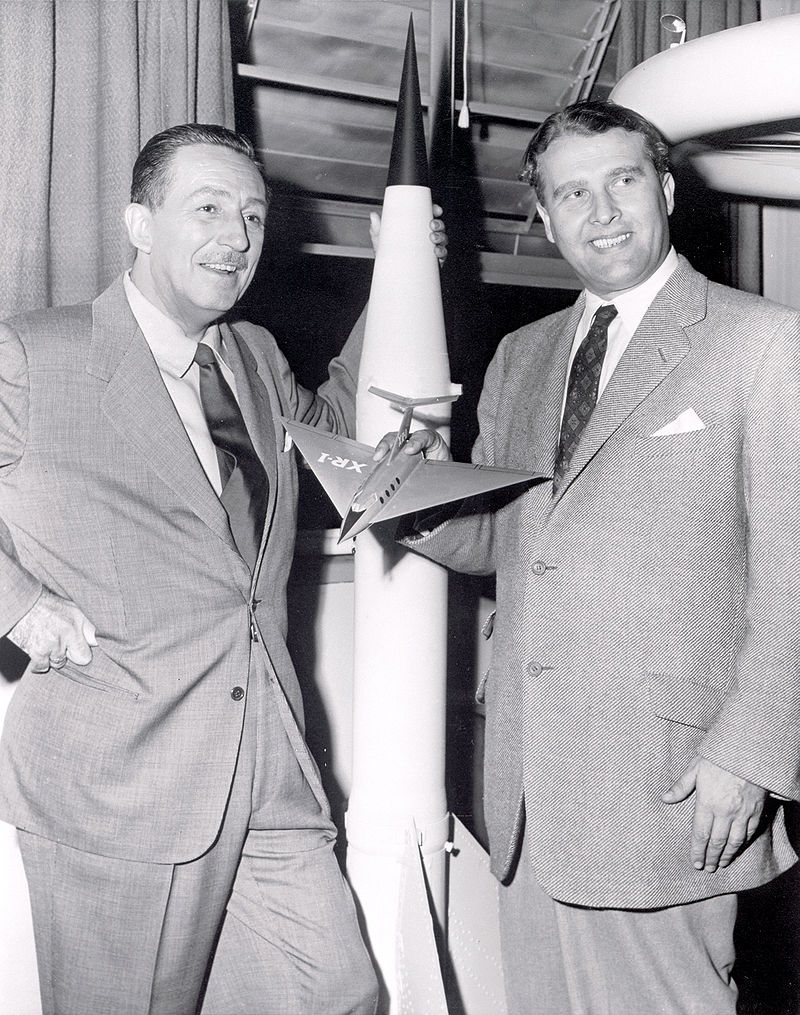

Walt Disney and Wernher von Braun, 1954.

VON BRAUN. Yes, but slave laborers have an unfortunate way of …

VON BRAUN. Yes, but slave laborers have an unfortunate way of … HITLER. Do you deny that you want

HITLER. Do you deny that you want