These days, any American with a functioning moral compass knows exactly how Hamlet felt when he said that. It’s a bit of a cliché that Shakespeare has something to say about virtually everything. So it’s hardly any wonder that we turn to Shakespeare’s eloquence and stories for insights concerning the catastrophe we now undergo.

But which play to choose, the selection being so rich?

Julius Caesar, the story of a tyrant brought low by his own ambition, has been a popular choice lately. Last year in New York, a production by the Public Theatre controversially (and unsubtly) portrayed the assassination of “a petulant, blondish Caesar in a blue suit, complete with gold bathtub and a pouty Slavic wife.” Richard III, with its Machiavellian antihero rising to power by nefarious means, is also much in vogue. And Professor Eliot A. Cohen recently likened Donald Trump to Macbeth, whose nearest allies turn against him as his criminal reign collapses.

Nobody ought to push any of these analogies too far. Donald Trump does not have the makings or the stature of a Shakespearean tragic hero. He has none of Julius Caesar’s nobility, Richard III’s articulate wit, or Macbeth’s introspective anguish.

A watercolor of King Lear and the Fool in the storm from Act III, Scene ii.

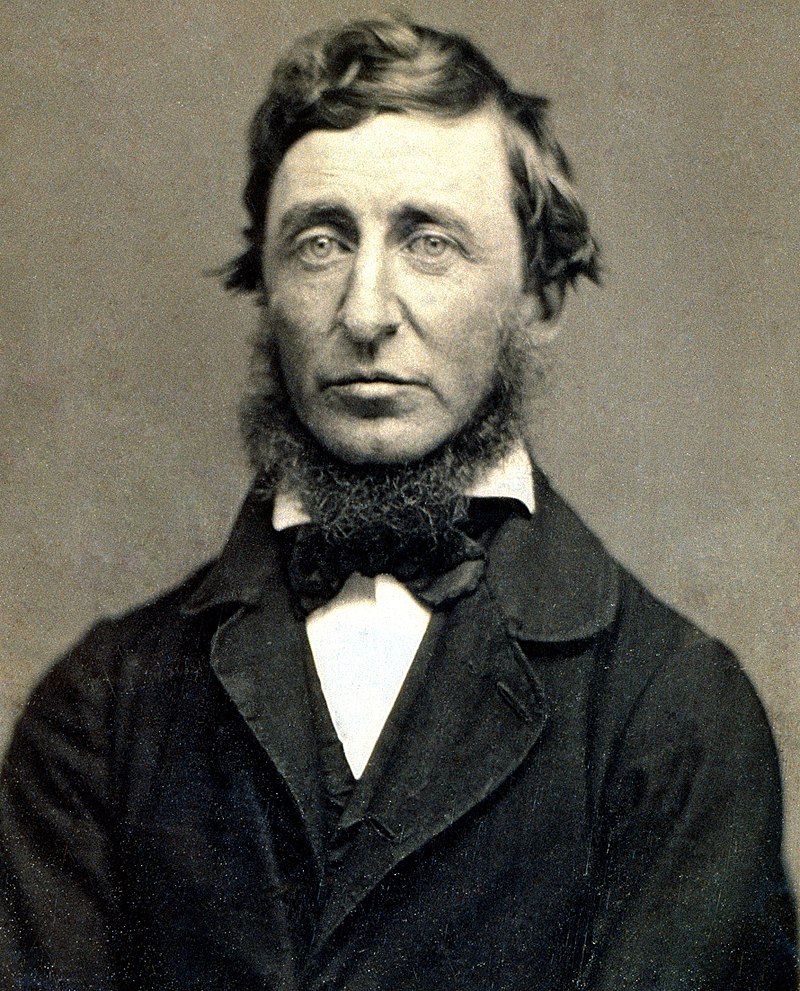

Nor does our president much resemble King Lear, who learns humility and decency in the depths of suffering and madness. Even so, it seems to me that King Lear speaks more about the crisis of Trumpism than any other Shakespeare play. And that, I think, is because King Lear has less to say about Donald Trump himself than it does about the world that is crumbling around him—and around us.

The story is familiar and deceptively simple, almost like a fairy tale. An old king foolishly decides to abdicate his authority and divide his kingdom among his three daughters. To decide which daughter will receive the greatest share of his kingdom, he puts them to a famous test …

“Which of you shall we say doth love us most …”

Lear rewards two daughters, Goneril and Regan, for their elaborate flattery, but he furiously disowns and banishes his favorite daughter Cordelia for her honesty and bluntness. Chaos ensues as Goneril and Regan subdue their father into beggarly destitution; he spends much of the play wandering through his forfeited kingdom in a state of madness—a madness which sometimes graces him with paradoxical wisdom. For example, in a moment of crazed lucidity, Lear captures the very essence of Trumpism …

LEAR. Thou hast seen a farmer’s dog bark at a beggar?

GLOUCESTER. Ay, sir.

LEAR. And the creature run from the cur—there thou mightst behold the great image of authority: a dog’s obeyed in office.

King Lear mourns Cordelia’s death, James Barry, 1786–1788

Lear’s abdication of authority creates a moral vacuum much like the one we inhabit right now—a vacuum in which norms of decency are threatened and largely destroyed. Catastrophe after catastrophe unfolds, tearing the kingdom to pieces and leading inexorably toward the play’s ultimate horrifying tableau—King Lear carrying his dead daughter Cordelia onto the stage, literally howling with animal grief before his own heart breaks forever.

During that last scene, the surviving characters are stricken with such despair that they wonder whether the world itself can endure …

KENT. Is this the promised end?

EDGAR. Or the image of that horror?

We might well wonder the same, for our situation is similarly dire. A manifestly egotistical and unstable man now has the power to unleash nuclear war. And faced with the possibility that the planet may soon become uninhabitable to humanity, Trump brazenly enacts policies that will hasten climate change.

Is there any hope at the end of Lear? Is there any hope for us now? Shakespeare’s nihilistic vision offers no easy reassurance. But there’s a strange idea lurking inside this savage play that merits parsing.

Three men are left standing at the end of King Lear—all of them capable of moral decency. King Lear’s exiled ally, the Earl of Kent, has spent the whole play loyally serving his master in disguise. The young Edgar, having survived his bastard brother’s machinations against him, has escorted his brutally blinded father to a peaceful death. Even Goneril’s husband, the once vacillating Duke of Albany, has at long last learned to follow the dictates of his conscience.

The task of rebuilding on the ruins of civilization finally falls to them.

Meanwhile—and I think this is terribly important—the evils that triggered and fueled the story’s chaos have been exhausted and destroyed. The Trump-like villains, duplicitous and opportunistic as they’ve been, have failed to stave off their own destruction. Obedient to their own vicious natures, they have inevitably turned their treachery against each other. Before they could quite destroy the frail, surviving goodness in the world, they have destroyed themselves.

The evil of Trumpism is already playing itself out in such a manner. Trump’s once-trusted allies—Michael Flynn, Michael Cohen, David Pecker, and Paul Manafort among them—are turning against him one by one. How could they do otherwise, given that their illusory loyalty was always founded upon self-interest, never on honor or decency?

So perhaps the grim denouement of Trumpism is already underway. Meanwhile, we who have witnessed this terrible spectacle with morally undeluded eyes must look to the future; it will be up to us to build upon the ruins.

King Lear, by an unknown artist.

Lear, in the depths of his suffering, may have a lesson to offer in this effort. Shorn of power, authority, possessions, and dignity, thrust out onto a storm-blasted heath to make his way like a beggar, Lear at last learns to empathize with those who suffer in oblivion …

Poor naked wretches, whereso’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your loop’d and window’d raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these? O, I have ta’en

Too little care of this! Take physic, pomp;

Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou mayst shake the superflux to them,

And show the heavens more just.

Like Lear, we have long “ta’en too little care of this,” leaving a moral vacuum in which Trumpism has arisen to run its ruthless course. To fill that vacuum, we must build a just and compassionate society.

It’s time to get started.

Q: What is

Q: What is