A poem of Wim’s just appeared in Visitant: “No More Flat Screens!“

A poem of Wim’s just appeared in Visitant: “No More Flat Screens!“

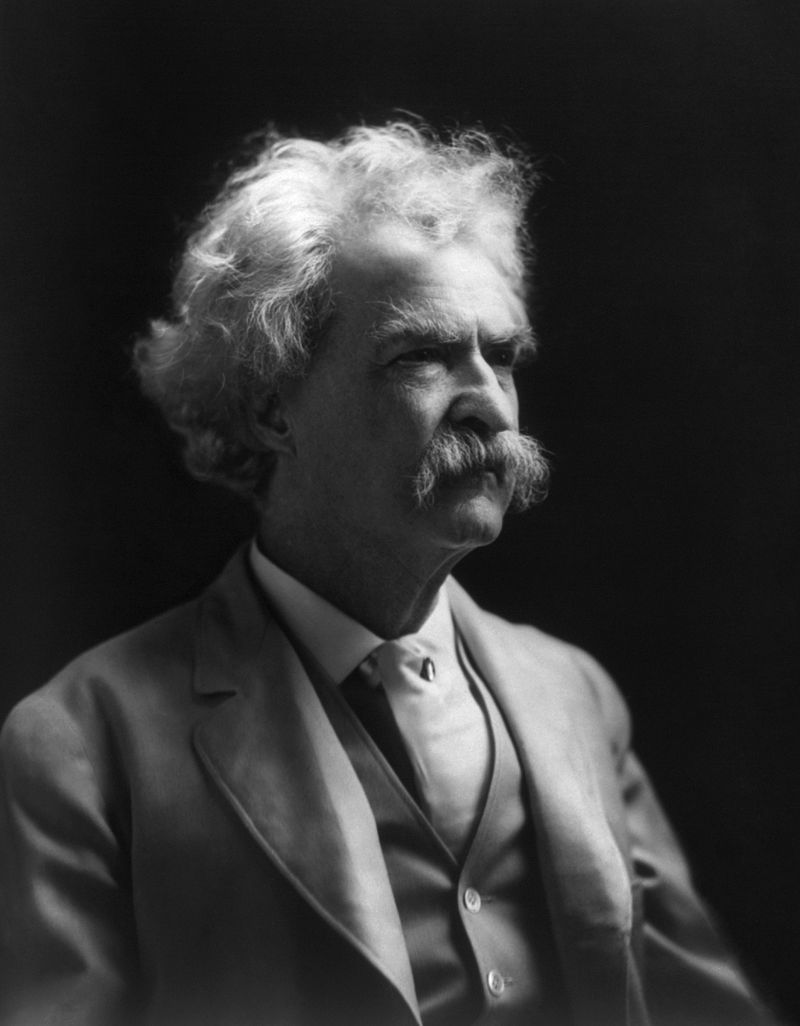

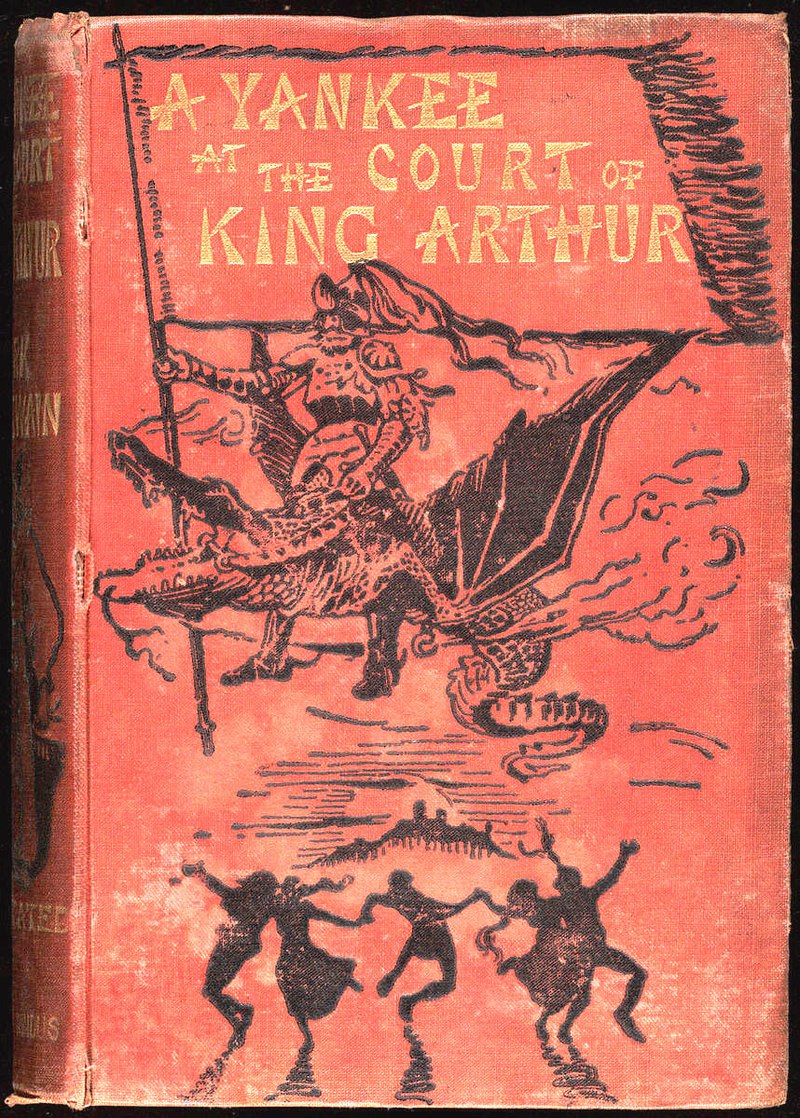

Every several years, I have to re-read Mark Twain’s novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court just to make sure I got it right. I don’t think I’ve ever read a book that’s so unlike its reputation, and it never loses its power to unsettle me. I finished re-reading it recently, and I found it to be especially disturbing in these dark days of Trumpism.

Every several years, I have to re-read Mark Twain’s novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court just to make sure I got it right. I don’t think I’ve ever read a book that’s so unlike its reputation, and it never loses its power to unsettle me. I finished re-reading it recently, and I found it to be especially disturbing in these dark days of Trumpism.

I suppose most of us have heard A Connecticut Yankee described as a light-hearted spoof of medieval chivalry, or a satire that pits Old World traditions against American innovation and ingenuity. The barebones story would certainly suggest just that. It’s the tale of Hank Morgan, an educated 19th-century Yankee with rare engineering gifts who gets magically transported back to King Arthur’s England, where he tries to bring things up to date.

As a premise, it sounds harmless enough. Indeed, Twain’s first mention of the idea in his notebooks suggests that he originally intended it that way …

Dream of being a knight-errant in armor in the middle ages. Have the notions & habits of thought of the present day mixed with the necessities of that. No pockets in the armor. No way to manage certain requirements of nature.…

As one might expect, the book does contain its share of burlesque humor. Knights roam through the kingdom wearing advertising placards for commodities like soap; they play baseball while wearing suits of armor; and Hank wins a jousting match by lassoing his opponents until he dispatches his last challenger with a pistol. In true Quixotic fashion, Hank’s future wife Sandy insists that he rescue a group of ladies held captive by a monstrous ogre—ladies who turn out to be pigs.

But as the narrative proceeds, Twain’s intentions seem to drift into more sinister realms. This isn’t unusual for Twain. Even his masterpiece, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, is notorious for its abrupt shifts in tone and mood. In later years, Twain confessed to his own limitations as a novelist …

But as the narrative proceeds, Twain’s intentions seem to drift into more sinister realms. This isn’t unusual for Twain. Even his masterpiece, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, is notorious for its abrupt shifts in tone and mood. In later years, Twain confessed to his own limitations as a novelist …

A man who is not born with the novel-writing gift has a troublesome time of it when he tries to build a novel. I know this from experience. He has no clear idea of his story; in fact he has no story.… So he goes to work.… But as it is a tale which he is not acquainted with, and can only find out what it is by listening as it goes along telling itself, it is more than apt to go on and on and on till it spreads itself into a book.

Twain was, after all, a live performer who entertained audiences worldwide with his lectures. He honed his literary technique as a teller of tall-tales that defied conventional narrative expectations of logic or consistency. He was an improv artist whose greatest works, A Connecticut Yankee among them, are really tall-tales enlarged to epic proportions.

To some readers, Twain’s seat-of-the-pants approach to novel-writing is a weakness. To me, it is a rare and original strength. As Pat and I often say, “Art is a way of finding out.” As he staggered through A Connecticut Yankee trying to find his narrative way, Twain found out a lot—about his story, his characters, himself, and all the rest of us. And what he found out wasn’t pretty.

For all its burlesque and low comedy, much of the latter half of A Connecticut Yankee focuses on the nightmarish realities of medieval life. Horror and comedy alternate at a dizzying pace during the memorable chapters in which Hank disguises King Arthur as a peasant and takes him on a tour of his own kingdom.

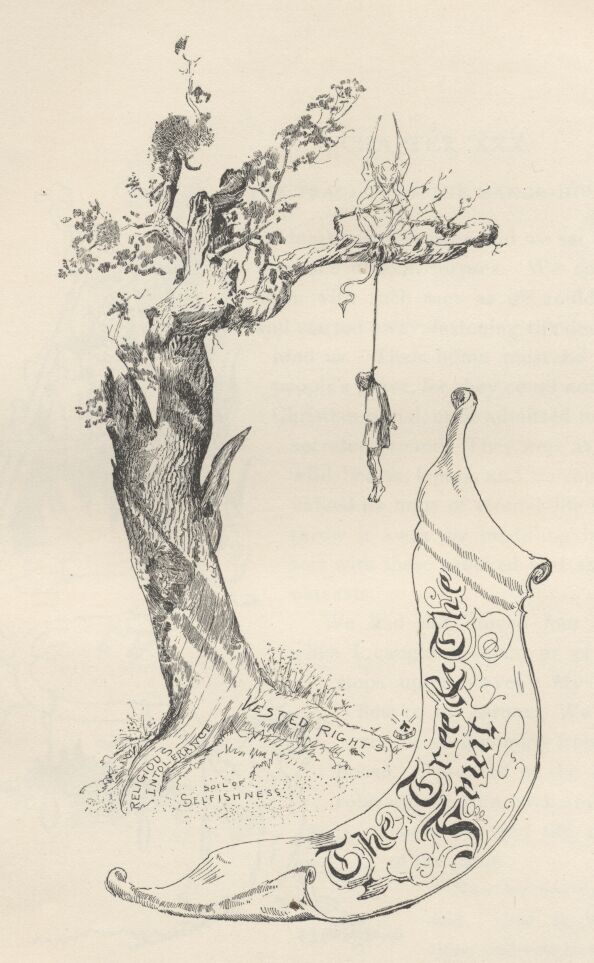

The king learns a number of grim lessons during this journey. He and Hank visit a peasant home in time to find its last family member dying from smallpox. They witness the hanging of a young woman whose only crime was stealing bread for her starving baby. When Hank and the king are unwittingly sold into slavery, they and their fellow slaves are offered relief from freezing weather at a stake where a woman is burned alive for witchcraft.

The king learns a number of grim lessons during this journey. He and Hank visit a peasant home in time to find its last family member dying from smallpox. They witness the hanging of a young woman whose only crime was stealing bread for her starving baby. When Hank and the king are unwittingly sold into slavery, they and their fellow slaves are offered relief from freezing weather at a stake where a woman is burned alive for witchcraft.

From the beginning, Hank maintains a smug sense of his own superiority as a visitor from a more rational time and place. He decides that he’s going to accelerate history itself and bring the 19th-century American blessings of education, industry, and democratic government to King Arthur’s Britain. In principle, he has nothing against achieving these ends through violence. Echoing Twain’s own personal sympathy for the French Reign of Terror, Hank muses …

There were two “Reigns of Terror,” if we would but remember it and consider it; the one wrought murder in hot passion, the other in heartless cold blood; the one lasted mere months, the other had lasted a thousand years; the one inflicted death upon ten thousand persons, the other upon a hundred millions; but our shudders are all for the “horrors” of the minor Terror, the momentary Terror, so to speak; whereas, what is the horror of swift death by the axe, compared with lifelong death from hunger, cold, insult, cruelty, and heart-break?

Even so, Hank hopes to carry out his own revolution through peaceful means. Working in secret to avoid the censorious eyes of the Church, he builds factories and schools and imagines that he’s making real progress toward ending the depredations and superstitions of feudalism. But after King Arthur dies and Hank declares Britain to be a republic, the Church reasserts its stranglehold on mass opinion and wipes all of his accomplishments away. And this leads to the novel’s dark and disturbing conclusion.

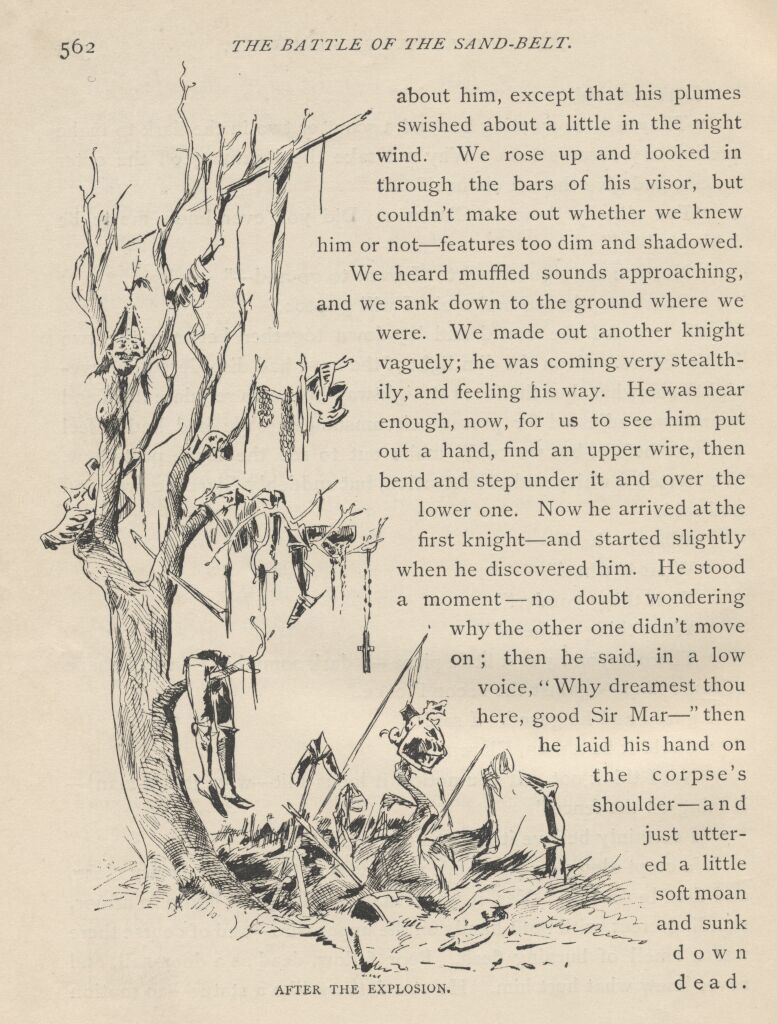

As they prepare for a final battle against the forces of chivalry, Hank, his apprentice Clarence, and 52 loyal young cadets take refuge in a cave, which they fortify with a moat, electrified wire, high explosives, and a battery of Gatling guns. Thousands of heavily-armored knights are blown up or electrocuted before the final charge, when the remainder of European chivalry must choose between a ditch suddenly flooded with water or a hideous storm of bullets …

As they prepare for a final battle against the forces of chivalry, Hank, his apprentice Clarence, and 52 loyal young cadets take refuge in a cave, which they fortify with a moat, electrified wire, high explosives, and a battery of Gatling guns. Thousands of heavily-armored knights are blown up or electrocuted before the final charge, when the remainder of European chivalry must choose between a ditch suddenly flooded with water or a hideous storm of bullets …

The thirteen Gatlings began to vomit death into the fated ten thousand. They halted, they stood their ground a moment against that withering deluge of fire, then they broke, faced about and swept toward the ditch like chaff before a gale. A full fourth part of their force never reached the top of the lofty embankment; the three-fourths reached it and plunged over—to death by drowning.

Within ten short minutes after we had opened fire, armed resistance was totally annihilated, the campaign was ended, we fifty-four were masters of England! Twenty-five thousand men lay dead around us.

It is a futile victory, to say the least. Hank and his followers are literally and hopelessly walled in by mountains of corpses. As the corpses decay, the cadets begin to sicken and die.

But Hank mysteriously survives to return to his own time and tell his tale. The magician Merlin, hitherto regarded by Hank as a fraud and a charlatan, creeps into the cave disguised as an old woman and murmurs a dark spell over the wounded and sleeping Hank …

“Ye were conquerors; ye are conquered! These others are perishing—you also. Ye shall all die in this place—every one—except him. He sleepeth, now—and shall sleep thirteen centuries. I am Merlin!”

What are we to make of this bleak and nihilistic denouement? And what does it have to do with Trump and Trumpism? I think one of the book’s earlier episodes hints at an answer.

During their incognito travels, the king and Hank witness a spree of mob violence in which many innocent people are butchered or hanged. The two travelers soon come across a group of children who are playing at hanging one of their own fellows with a makeshift noose. The king and the Yankee manage to rescue the hanged child just in time to save his life. As Hank observes …

It was some more human nature; the admiring little folk imitating their elders; they were playing mob …

I think, as he wrote A Connecticut Yankee, Twain found himself increasingly faced with grim realities of what he eventually described as “the damned human race.” Human beings aren’t cruel, bigoted, and violent by nature, but they are by nature ignorant, and they can be easily persuaded to cruelty, bigotry, and violence under one another’s influence. This is why history can seem so hopelessly cyclical in its repeated patterns of civilization and barbarism, enlightenment and superstition. In the end, Hank himself falls prey to this cycle by wreaking apocalyptic destruction upon King Arthur’s England, and also in his final enchantment by magic in which he knows better than to believe.

We are living out much the same situation in today’s America. In a nation steeped in the ideals of tolerance, equality, liberty, and justice for all, many of us are forsaking those very ideals under the influence of vile and unscrupulous leaders. We are in danger of rejecting all that is best about America. Can we escape this repetition of historical forces? Maybe—but not, I think, without fully understanding those forces. A Connecticut Yankee is an invaluable guide toward such understanding.

But for all its humor—and there is much humor in Twain’s novel—it is bitter medicine. Twain may have spared us the bitterest of his vision, remarking privately that he would need “a pen warmed up in hell” to share all of it. As Hank himself observes late in the book …

Lord, what a world of heartbreak it is.

—Wim

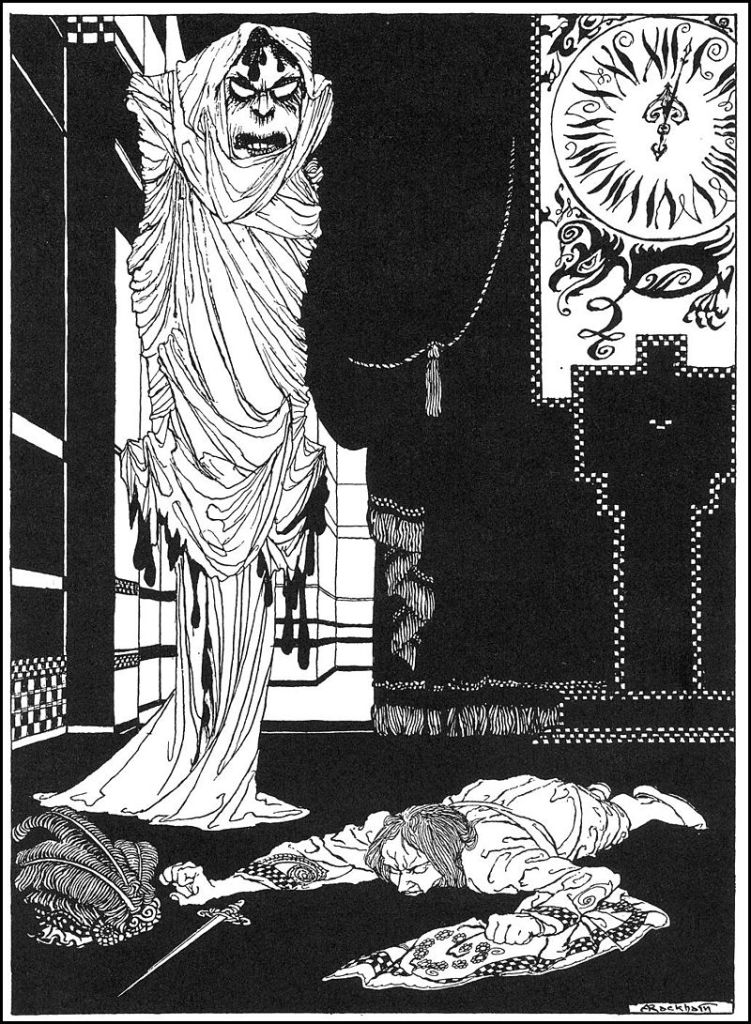

And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death

held illimitable dominion over all.

At the last midnight ever to fall,

the clock’s brazen lungs swelled full

and exhaled twelve sonic ebony sighs

that shuddered against the welded gates

and made the airtight abbey shake.

The dancers halted stupefied

and the music hobbled to a hush

at the advent of the uncanny guest

in his cadaverous eyeless mask

clad in the vesture of the grave.

Who presumes, who makes so bold?

Who dares dishonor this masquerade

of laughter and Terpsichore

and lotos-devouring lunacy

with uninvited grief and thought?

So cried the Prince, chasing the stranger

through his seven suites bedight

in lapis blue and lavender,

in emerald and tangerine,

in ivory and heliotrope,

until, in a chamber of sable velvet

glowing vermillion by fiery braziers

shining through panes of tinted glass,

the Prince cornered and challenged him,

guise to guise and mask to mask.

You! Profaner of mockeries,

delinquent in mandatory scorn—

kneel before your sovereign lord;

prepare your flesh for my dagger’s delight,

your blood to quench these stones!

But neither stones nor knife were sated,

and the Prince ached with unbidden sorrow.

How strange, he thought, that any mischance

should visit so noble a potentate,

so wise, so frugal, and so great.

Why, he wondered, should he be sad,

sequestered with his chosen kindred

while the Red Death raged outside?

He gazed upon the faceless stranger,

whose very silence made reply.

You fail to recognize me, sire?

Does the Prince deny his faithful son?

I’ve been too long from home, I fear.

But how could you forget a child

hatched fully grown from your lifeless heart?You nourished me at your barren breast;

I learned all things at your cruel feet;

all that you are, so I must be;

what your will would have, so I must do;

thus I have served you throughout your realm.

No soul survives in Greed’s dominion;

No children play in the empire of Hate.

No life throbs in the kingdom of Conceit.

Do I appear in the guise of Death?

I am yourself—manifest, incarnate.

The privileged revels now all ended,

the stranger crumbled into dust.

The Prince retraced his wending steps

through the mute particolored suites

and found his merry throng all slain.

But tender no tears for the Prince;

rather you may envy him,

for Hell is Heaven for the Damned.

He abides in welded, airtight bliss

within his castellated walls

roaming among those putrid remains

(worthy companions at long last!)

sheltered forever from all he dreads—

new buds, new blossoms, new hopes, new laughter,

all bourgeoning amid death’s decay.

—Wim

Working in isolation and without an ordinary outlet seems to be uncomfortable to lots of people, but might be more familiar for artists and writers. Why have we been doing that kind of thing for so long? The question reminded me of an essay from some years back that took the form of a conversation among people waiting for an art class to begin, as told by a first-person narrator. It was the only piece accepted for this anthology that was told in a creative form.

Here are some lines from the ending of my essay “Reveyesed I’s,” written for the publication Creativity:

Just as Roger and Rose Ellen are leaving together, Roger turns back and looks at Marie. “Why did they persist? Why do you?” he asks.

“What?” asks Marie.

“Why do artists insist on making art, without pay or recognition?” Roger asks.

“Why is art made, when the artist is no longer employed to fill the needs of church or king? Why, when there are no animals to be entranced, no hunting spells to weave by firelight deep beneath the earth? When images can more quickly be made by other means?” the model chants.

“When there is no clear use for what they do?” Roger asks.

“The artist needs to get the intuitions of the mind outside, and see what they look like. Or hear what they sound like,” Marie answers.

“Thoughts grow and change as they emerge. The process of getting the images down is a process of knowing them better. It’s a way of coming to terms with the shifting and expanding nature of reality,” the model says.

“What does creativity have to do with reality?” Kay asks.

“I think that the relationship of art to reality lies in the creative act itself. It’s not in the images or other results produced. The creation of images is part of the learning process, not something carried out after it,” says Marie.

“Just for themselves, then?” asks Roger.

“Oh, no. The response of others adds to the meaning. When readers and viewers make their own meanings, they are also involved in the process,” says Marie. …

“But what does all of that have to do with living in the real world?” Kay asks.

“It is by focusing on the process of creating works of art, and by drawing the viewer into that process, that our arts represent the real world. They reflect the way that we function in that world,” says the model. She returns to her place among the still-life items.

The model sits still for a long moment, then shifts her position. She speaks slowly, “‘No longer to receive ready-made a world completed, full, closed upon itself, but on the contrary to participate in a creation, to invent in his turn the work and the world, and thus to learn to invent his own life.’” She says nothing more. But that last, I am sure, was a quote from Robbe-Grillet. I shall have to look it up.

Marie nods. She gets slowly to her feet and gathers up her belongings. “My grandson is coming for me after class. But that’s still a long time off.”

“I’ll give you a ride home,” says Karen.

“Are there artists now, discovering?” asks Olivia.

“I hope so. I trust there must be,” says Marie. Once more, we glimpse through her glasses the multiple lights reflecting off her eyes.

Karen and Marie go out together. Kay and Olivia remain for a short time, talking quietly. Am I mistaken, or do I see there a slight glitter, a hint of a change in the eyes?

Then they, too, go out into the dark.

(See our Books and Downloads page for the whole essay.)

Pat

Troubled times often lead to exciting innovation in the arts. Right now, creative people are dutifully quarantining themselves, just like the rest of the public. And yet at the same time, they’re refusing to sit back and wait for some kind of magical “all clear” signal before going back to work. This is especially true in the performing arts. Although bricks-and-mortar theaters and other performance venues have gone dark and dormant, there has been an explosion of virtual performances.

Songwriters, musicians, and other performers are going digital and online to reach out to a public that is hungrier than ever for artistic experience. Billboard, Grammy.com, Creative Capital, and other sites keep ongoing, updated lists of online digital artistic events.

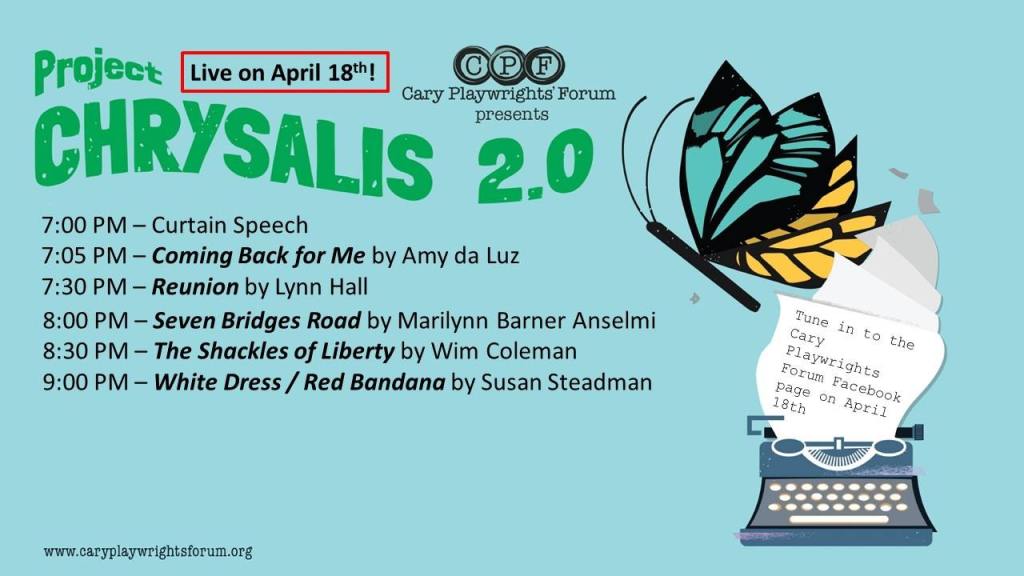

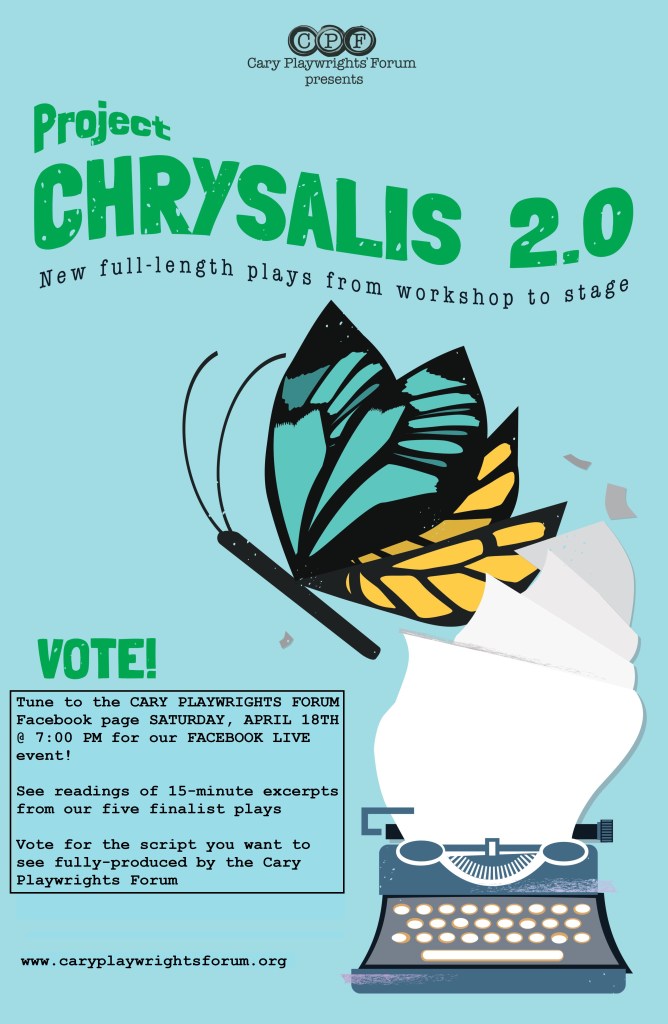

I am excited and honored to be involved in an upcoming live, digital theater event. Project Chrysalis 2.0, an evening of staged readings of scenes from new plays, is going to take place online. An excerpt from my award-winning play The Shackles of Liberty will be one of five new works featured. For both rehearsals and performances, participants are working as an ensemble while remaining safely quarantined in their homes. I’m enjoying these unique, innovative, and rewarding rehearsals and am excited about the upcoming performance.

Hosted by the Cary Playwrights Forum, these scenes will will be broadcast live via Facebook Live on Saturday, April 11, at 7:00 p.m. Afterwards, the audience will vote on which play will get a full production. Please join us for this exciting and special event!