It’s been almost five years since I posted some thoughts about Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court and how it relates to our times. Revisiting those thoughts today, they seem even more sadly apt than they were back then.

A Connecticut Yankee is mysterious and disturbing book, so unlike its reputation that one can only assume that few people really bother to read it. It starts off as a light-hearted satire of medieval times and climaxes with an apocalypse of sorts—the mass slaughter of Europe’s knight errantry by electrocution, dynamite, and a Gatling gun.

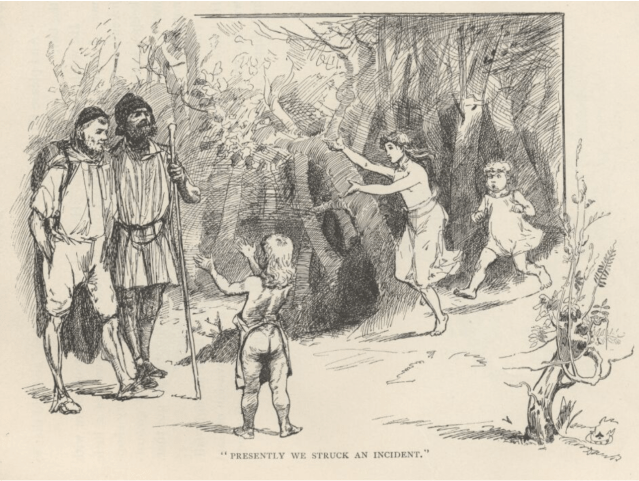

But perhaps the book’s most unsettling episode involves children. When the protagonist, Hank Morgan, takes King Arthur on an incognito tour of the brutal realities of his kingdom, they witness a spree of mob violence in which peasants turn against peasants, butchering and hanging one another out of blind fear of their rulers. The next day, Hank and the king come across this scene:

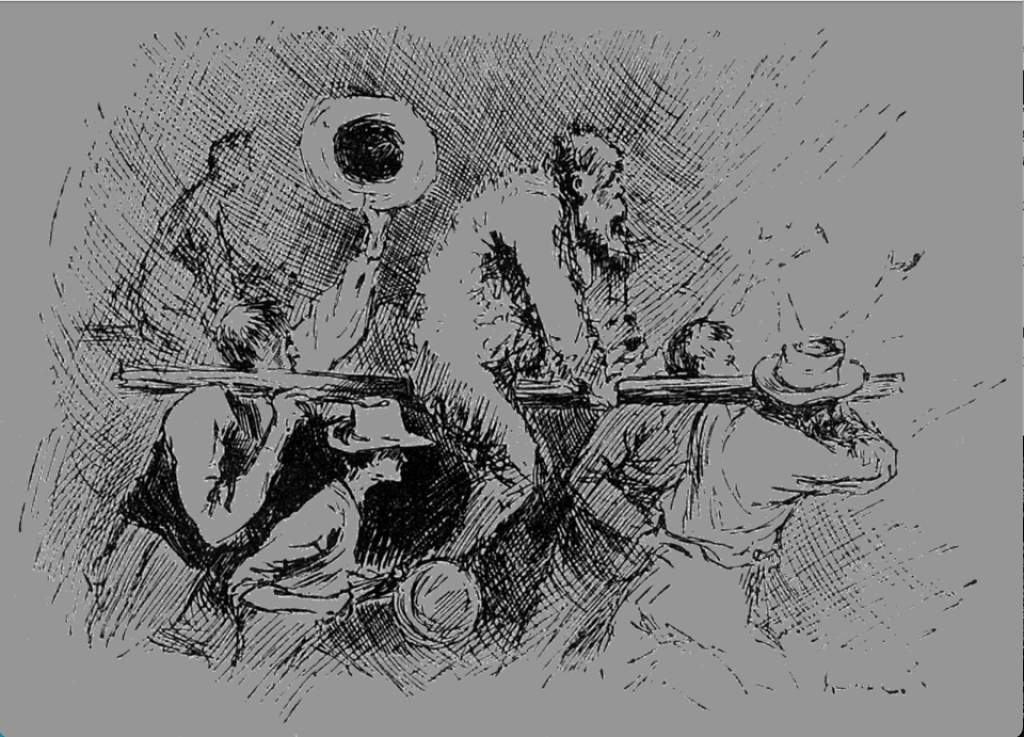

A small mob of half-naked boys and girls came tearing out of the woods, scared and shrieking. The eldest among them were not more than twelve or fourteen years old. They implored help, but they were so beside themselves that we couldn’t make out what the matter was. However, we plunged into the wood, they scurrying in the lead, and the trouble was quickly revealed: they had hanged a little fellow with a bark rope, and he was kicking and struggling, in the process of choking to death. We rescued him, and fetched him around. It was some more human nature; the admiring little folk imitating their elders; they were playing mob, and had achieved a success which promised to be a good deal more serious than they had bargained for.

Twain’s account of children hanging one another to imitate their elders is truly a fable for these days of Trumpism. The question is often asked: Do you want your children to behave like Donald Trump, with his blatant narcissism, bigotry, misogyny, name-calling, cruelty, bullying, crooked dealings, and interminable lies? While few Americans would admit it aloud, I suspect that an alarming number of them want exactly that. As Elon Musk himself said to Joe Rogan, “The fundamental weakness of western civilization is empathy.”

Specifically, empathy is held suspect in male children. It’s an idea that’s deeply ingrained in our culture—that empathy, fair play, and kindness are for sissies and “girly men.” Boys must instead be taught the opposites of all those traits in order to grow up to be “real men”—men with power, fame, and wealth like Donald Trump. Life is a zero-sum game, and “nice guys finish last,” and to be a man, one must never show weakness, shame, or scruples, nor ever concede defeat.

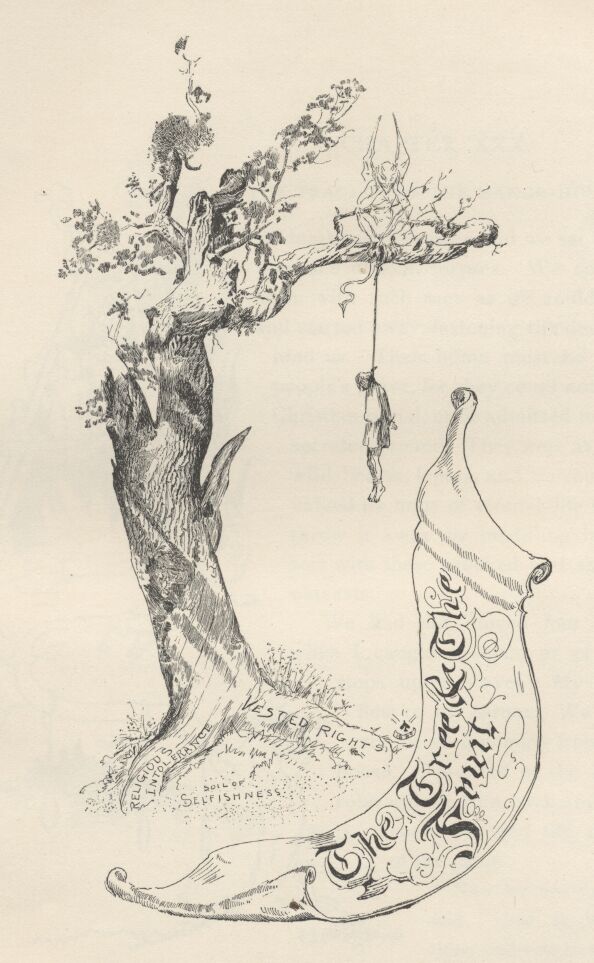

We often say of Trumpism that “the cruelty is the point,” especially when it comes to the treatment of immigrants and their families. But Twain wanted us to believe that cruelty is not innate but learned, and that childhood is the aptest time to teach it. In “The United States of Lyncherdom,” a polemic Twain wrote to protest the rise of murderous violence against African Americans, he tried to explain the viciousness of mobs as motivated by moral cowardice, not pleasure:

Why does a crowd … by ostentatious outward signs pretend to enjoy a lynching? Why does it lift no hand or voice in protest? Only because it would be unpopular to do it, I think; each man is afraid of his neighbor’s disapproval — a thing which, to the general run of the race, is more dreaded than wounds and death.

As bitter as Twain became toward “the damned human race,” I fear that he remained naïve about human nature. Cruelty may well be indeed learned and imitated, not innate; but once it takes root, it becomes an illness, an addiction. Some addicts don’t merely pretend to enjoy their drug of choice; they convince themselves of it.

As Huckleberry Finn put it upon witnessing an act of mob violence, “Human beings can be awful cruel to one another.”

—Wim