Characters:

René Descartes

Queen Christina

The scene is the royal library in Stockholm, Sweden, on February 1, 1650, at about 5:00 a.m. Queen Christina is dressed in male attire. René Descartes enters, bows to the queen, and begins to speak. He shivers almost convulsively, despite being warmly clothed. He is extremely ill and coughs frequently.

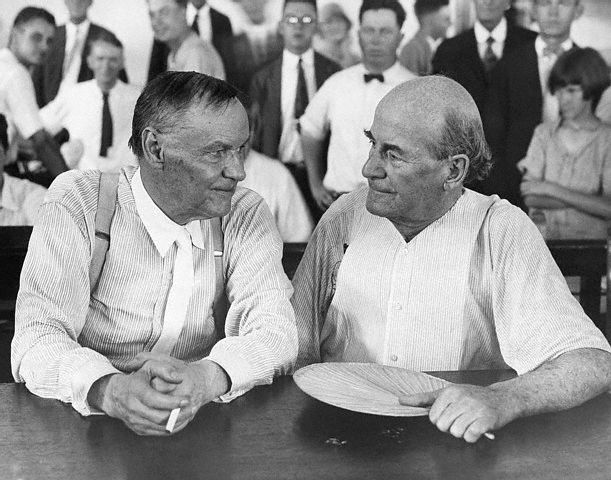

Queen Christina (left) and René Descartes (right)

DESCARTES. Your Majesty, I have a regrettable announcement to make. I’m not long for this world. Your royal physicians have told me so. These morning lessons of ours are to blame. I’m 54 years old and have never been in robust health. As you know, it was long my custom to stay abed mornings till nearly noon, meditating upon my work. But you insist that I meet you here at 5:00 in the morning. Before that ungodly hour, I must rise, bathe, and dress. And while I am still damp from bathing, I must walk here to your library, out-of-doors in this northern cold that freezes men’s very thoughts. I am burning up with fever. I cannot stop shivering. My lungs are inflamed. Your doctors tell me that my only hope of survival is your royal mercy. Please, please, Your Majesty, allow me a few more hours of sleep. Allow me to tutor you in the afternoon. And may we not light the fireplace? And may we not close some of these windows?

CHRISTINA. I learn best in the cold.

DESCARTES. But Your Majesty—

CHRISTINA. Stop calling me that, Monsieur Descartes. It infuriates me. I am the only woman alive who knows your analytic geometry. You dedicated a book to me. We’ve discussed the mysteries of the universe. We’ve probed each other’s intellects in their full nakedness. That makes us lovers. I am your mistress, not your queen. So call me your beloved darling—no, your precious little squirrel. I command it.

DESCARTES. Your Majesty, that would be—unthinkable.

CHRISTINA. Do it.

DESCARTES. Yes, my … precious little squirrel.

CHRISTINA. Now stop whining about your paltry little ailments. Something terrible has happened. I’ve committed a frightful deed. I don’t know how to live with myself. Sit down.

(DESCARTES does so. CHRISTINA hands him a saucer and a magnifying glass.)

CHRISTINA. Tell me what this is.

DESCARTES (looking in the saucer through the glass). It looks like a tiny pink pinecone.

CHRISTINA. You should know what it is.

DESCARTES. A pineal gland?

CHRISTINA. It came from my dear tomcat, Loki.

René Descartes

DESCARTES. You killed your cat?

CHRISTINA. He was terribly sick. His eyes were sunken and had lost their luster. He couldn’t lift his backside off the floor, not even to relieve himself. He was suffering terribly, and I knew he would never get better. So I held him close, and said goodbye to him, and broke his neck with a twist of my hand. Then my curiosity got the better of me, and I opened his skull with a paring knife to see what was inside. And there I found this between the lobes of his brain. I thought I was putting him out of his misery. But it turns out that I murdered him.

DESCARTES. You did not murder Loki.

CHRISTINA. Why not?

DESCARTES. One cannot murder a brute beast.

CHRISTINA. Why not?

DESCARTES. Because a brute beast does not have a soul.

CHRISTINA. This brute beast had a pineal gland. The pineal gland is the seat of the soul. You’ve said so yourself.

DESCARTES. Not the seat of the soul precisely. More like a gateway. It connects the sensory realm of matter, space, and extension with the spaceless dimension of spirit, soul, and thought.

CHRISTINA. The dimension of God.

DESCARTES. Indeed.

CHRISTINA. Loki had a pineal gland. Therefore, Loki had a soul. Therefore, Loki had access to that spaceless dimension. Therefore, Loki was connected with God. Therefore, I murdered him.

DESCARTES. Not so, lady, not so. Didn’t you read that book I wrote for you? An animal is nothing more than a wonderful machine of nature. It cannot think or feel. You could have cut open Loki’s skull and poked about his brain while he was fully alive without causing him the slightest distress. I practice this sort of thing myself. Would I ever sanction murder? So put your mind at ease. And please, please, call a servant to start a fire and shut these windows.

CHRISTINA. You haven’t explained why a soulless creature’s brain should contain a gateway of the soul.

DESCARTES. And I shall explain, my precious little squirrel. But not now, not while I am so sick. I beg you, if you love me with a true mistress’s love, if you don’t want me to die—

CHRISTINA. Oh, stop fretting about death.

DESCARTES. Then you do want me to die. That’s exactly it. You are stalking me. You are awaiting the moment for the kill. When I weaken enough, you’ll snap my neck, just like your cat’s. And then you’ll dissect me to compare the insides of our skulls, won’t you?

(Pause)

CHRISTINA. It hadn’t occurred to me.

DESCARTES. Dear God!

Cover of Descartes’ Meditations on First Philosophy

CHRISTINA. I’m starting to understand. It’s all coming clear. This whole pineal body-mind duality business, this separation between the material and the mental, you made it all up.

DESCARTES. Why would I do such a thing?

CHRISTINA. Naturally, as a materialist and a mechanist, you’re afraid the churchmen will discover that your learning leads directly to atheism. You are afraid of being burned at the stake like Galileo.

DESCARTES. You mean Giordano Bruno.

CHRISTINA. No, I mean Galileo. Something bad happened to him too, didn’t it?

DESCARTES. He was forced to keep quiet.

CHRISTINA. Even worse. I warn you, don’t try to deceive me. I did not bring the most brilliant scholar in Christendom to my court so he might hoodwink me along with everybody else. I mean to learn the truth. About everything. At all costs. Now if you value your life, tell me what you know!

DESCARTES. The gland—it is exactly what I’ve said.

CHRISTINA. It makes no sense.

DESCARTES. Then what other purpose might it serve?

CHRISTINA. Perhaps it is vestigial of some long-defunct use. Let us suppose that Loki and I had a common ancestor—

DESCARTES. Cousins? You and your cat?

CHRISTINA. And you. And a dog. And a mouse. And a precious little squirrel. Every creature that has a pineal gland.

DESCARTES. But, oh, noble lady—!

CHRISTINA. I know, I know. “And God said, Let the earth bring forth the living creature after his kind.” And here I am, proposing that God’s eternal kinds are mutable, that they evolve. But let’s be just a wee bit heretical, shall we? Just between ourselves. This is neither Catholic France nor Calvinist Holland, but simple, backward, rustic, Lutheran Sweden, where scarcely anybody has brains enough to be bigoted. Whatever we say won’t leave this room. And if it does, and if the Inquisition catches you—well, I promise to be burned at the very same stake right along with you, and won’t that be fine? Again, let’s suppose that you and I and Loki had a common ancestor. Whatever such a creature was, it had some use for the gland. Perhaps it was a sort of eye, just like the mystics say. That use disappeared, but the gland did not. And now it just sits there wedged in our brains, doing nothing in particular. There is no gateway to the soul.

DESCARTES. Blasphemy.

CHRISTINA. How so?

DESCARTES. You are on the brink of saying—

CHRISTINA. What? That there is no soul? That there is no God? Nay, perhaps simply everything—this entire exquisitely manifold and sundry material world of ours—is nothing but soul, is nothing but God.

DESCARTES. It is atheism either way.

Queen Christina

CHRISTINA. Nonsense. It is piety multiplied. We must worship the body, because it creates mind. We must worship mind, because it is capable of worship. We must worship all immanence, because it is God. When we go into a church, we must sing hymns of praise to its very stones, for they too are the stuff of divinity, restlessly striving for mind and for life. If I am wrong, you must explain to me why.

DESCARTES. I haven’t the strength.

CHRISTINA. Then you’ve proved my point. Your body and your mind are one. Otherwise your mind would be impervious to the sickness of your body. Your body is about to die; therefore your soul is about to die. Or might your soul instead assume some other material shape?

DESCARTES. I shall lose consciousness.

CHRISTINA. Oh, do! Please! I must observe that! (Pause) Could you teach me how to lose consciousness too? I want to know what it’s like.

END OF PLAY

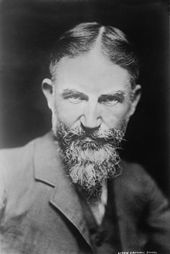

It might seem like a rather big leap from our previous two blog posts to this one — from the Bible-thumping Bryan to the vitalist Shaw. But consider what Shaw had to say about the theory of Natural Selection:

It might seem like a rather big leap from our previous two blog posts to this one — from the Bible-thumping Bryan to the vitalist Shaw. But consider what Shaw had to say about the theory of Natural Selection: This is from the preface to Shaw’s monumental five-play cycle Back to Methuselah, written some six years before Bryan took the witness stand in Dayton, Ohio. Of course, he and Bryan had both fallen for a gross caricature of what Daniel Dennett calls “Darwin’s Dangerous Idea.” But that’s hardly a surprise. Theirs was the heyday of “Social Darwinism,” the idea that “might makes right” in human society as well as in nature.

This is from the preface to Shaw’s monumental five-play cycle Back to Methuselah, written some six years before Bryan took the witness stand in Dayton, Ohio. Of course, he and Bryan had both fallen for a gross caricature of what Daniel Dennett calls “Darwin’s Dangerous Idea.” But that’s hardly a surprise. Theirs was the heyday of “Social Darwinism,” the idea that “might makes right” in human society as well as in nature. Bryan and Shaw were of sharply opposing mentalities, to put it mildly. Even so, they were both men of faith for whom the idea of a universe devoid of meaning was intolerable. But Shaw’s faith, unlike Bryan’s, was by no means conventional. As he wrote to Leo Tolstoy,

Bryan and Shaw were of sharply opposing mentalities, to put it mildly. Even so, they were both men of faith for whom the idea of a universe devoid of meaning was intolerable. But Shaw’s faith, unlike Bryan’s, was by no means conventional. As he wrote to Leo Tolstoy,