Tell us a bit about yourself – something that we will not find in an official author’s bio?

My father was a theater professor, director, playwright, and actor, so my very earliest memories are of attending play rehearsals. In a primal sort of way, this shaped how I’ve developed as a creative storyteller, whether I’m doing fiction, drama, or poetry. It also helped shape my growth as a person and how I view reality. Starting at the age of two, I watched actors slip in and out of character, oftentimes repeating the same actions and words over and over again, but in endless variations. These experiences left me with a lot of lifelong questions and obsessions. For example, what are the boundaries between life and performance, reality and imagination? How much of what we do every day and all the time is acting, and how much of it is really living—and is there really any difference? All my life I’ve observed those boundaries as constantly shifting. I’ve also come to see life itself as an act of creative storytelling.

My father was a theater professor, director, playwright, and actor, so my very earliest memories are of attending play rehearsals. In a primal sort of way, this shaped how I’ve developed as a creative storyteller, whether I’m doing fiction, drama, or poetry. It also helped shape my growth as a person and how I view reality. Starting at the age of two, I watched actors slip in and out of character, oftentimes repeating the same actions and words over and over again, but in endless variations. These experiences left me with a lot of lifelong questions and obsessions. For example, what are the boundaries between life and performance, reality and imagination? How much of what we do every day and all the time is acting, and how much of it is really living—and is there really any difference? All my life I’ve observed those boundaries as constantly shifting. I’ve also come to see life itself as an act of creative storytelling.

Do you remember what was your first story (article, essay, or poem) about and when did you write it?

Again, my roots are in theater, so instead of getting published, I watched my plays go into rehearsals and production. Putting words on a page and then turning them over to actors is a true acid test. Putting those words in front of an audience takes things to an even tougher level. The process has taught me to make hard demands of myself as a writer, and to invent many personal rules of thumb. For example: If what you write is hard to speak aloud, it isn’t as good as it should be. Keep writing and saying it over and over again until it tastes good.

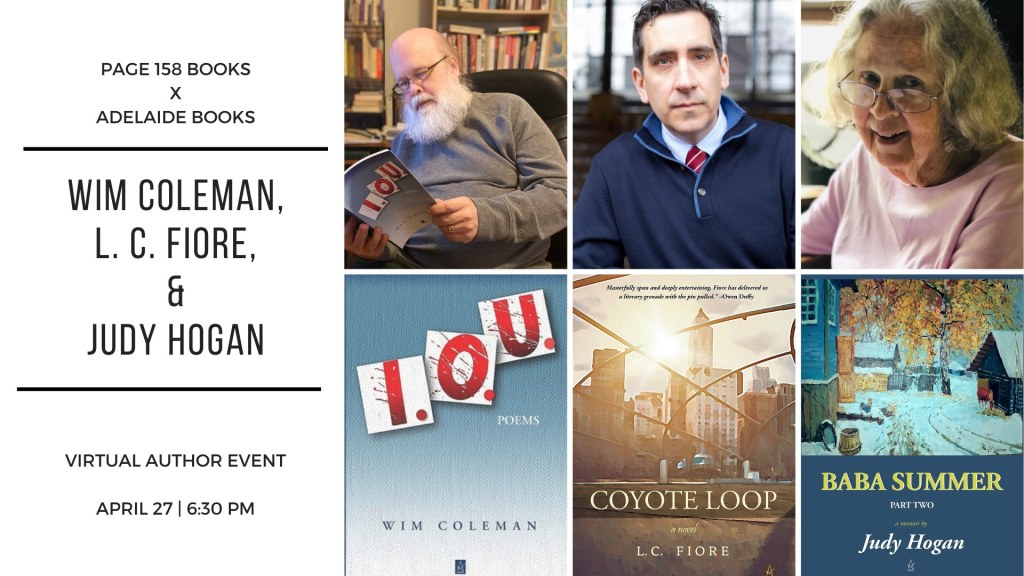

What is the title of your latest book and what inspired it?

It is called I.O.U., and it is my first collection of poetry. Although it’s a diverse and unruly bundle, it explores a single theme that permeates all of my writing, whether in fiction, nonfiction, drama, or poetry. That theme is Story (with a capital S). As my wife, Pat Perrin, and I once put it in a collaborative essay,

“Storytelling, like all art, like life, is an act of learning—of finding out. We are mistaken to assume that stories of transformation are only about transformation, mere illustrations. Instead, they are transformation itself, acts of practical alchemy, with the power to alter the reality of every receptive person they touch. (That’s why we must learn to recognize a hate-based tale in any garb, and admit that nothing holy feeds on pain.) As we live our stories and tell them, we learn what they are about … and they change … and they transform.”

That’s what all of my poetry is about. The title poem, “I.O.U.,” is a promise to stay true to this lifelong purpose.

How long did it take you to write your latest work and how fast do you write (how many words daily)?

I.O.U. is selection of poems I’ve written over the course of some 40 years. And some of the individual poems took almost that whole time to write, or at least to revise until that I was fairly happy with them. I don’t write many poems at one sitting. Only a few have popped out pretty much spontaneously. They often start that way, but the polishing can take years and years.

Most of my current writing, though, consists of ghostwriting. I do almost all of that in collaboration with my wife, Pat Perrin. We average more than 1000 words a day together doing that sort of work, sometimes much more. A couple of days ago we hit 7000 in order to make a deadline.

Do you have any unusual writing habits?

I suppose the most unusual aspect of my writing is that I do so much of it in collaboration. Pat Perrin and I have been writing together for more than 30 years, and we’ve published well over 100 books, including some that have gotten good attention, for example The Jamais Vu Papers (Crown, 1991), which has become something of a cult classic. Terminal Games (Bantam, 1994), which we wrote under the pseudonym Cole Perriman, was published in five foreign translations, discussed by literary critic N. Katherine Hayles in How We Became Posthuman, and taught in courses about literature and contemporary culture at several leading universities.

Is writing the only form of artistic expression that you utilize, or is there more to your creativity than just writing?

Is writing the only form of artistic expression that you utilize, or is there more to your creativity than just writing?

I draw when I can. I wish I had time to do a lot more drawing. I find it to be wonderfully meditative. A non-verbal form of artistic expression helps me to tap into brain areas that I don’t explore as much as I should. It actually makes me a better writer.

Authors and books that have influenced your writings?

The mind boggles! I don’t know where to begin, except to say that some of the thinkers who have had the most impact on me have not been poets, playwrights, and fiction writers, but philosophers, scientists, and historians. The psychologist Julian Jaynes’s 1976 book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind has shaped my worldview in ways that impact my work (and my life) every single day. I believe that many other writers, especially poets, feel the same way about Jaynes. He offers a revolutionary view of history, psychology, and human nature that challenges all kinds of received wisdom. Jaynes is also very controversial, but his ideas have achieved greater widespread acceptance than his critics like to admit. I tend to notice that most of his detractors don’t seem to have bothered to read his book. Reading his Origin a few decades ago blew my mind and changed my world. I’ve been reeling from it ever since.

What are you working on right now? Anything new cooking in the wordsmith’s kitchen?

I’ve been moving back toward writing drama lately. Weirdly, this is in part due to Covid and the isolation it has wreaked on everybody, especially people in the performing arts. In mid-2020, I was invited to join a “Cyber Salon” of amazingly gifted people, including multi-talented actors, poets, directors, and playwrights. Because they haven’t been able to get together for live, in-person performances, they’ve started meeting on Zoom. I’m lucky and honored to have been invited to join them. Every week we present some of our work to each other. For the first time in years, I’ve been able to hear my dramatic writing read and interpreted by actors again. It has been truly thrilling—and of course, often scary. I’m currently writing a full-length play which I’m working on with the Salon, and which I’m not ready to talk about yet.

Did you ever think about the profile of your readers? Who reads and who should read your books?

I think my poetry (and my other writing) appeals to people who are hungry for stories and metaphors for our troubled times, for something beyond a steady diet of what currently rates as literary. I’m sometimes told that my work fills a personal and cultural need. I certainly hope so. My typical readers are well-read but are not necessarily academically inclined. They read primarily for enjoyment, information, and enrichment. They also enjoy a fair amount of mental stimulation.

Do you have any advice for new writers/authors?

Never finish your apprenticeship. What I mean is, never get complacent in your assumptions of “mastery.” When it comes to poetry, take time to experiment with technique—with rhythm, rhyme, meter, and various forms. Study examples of all of these techniques. They’ll force you to deal with language in ways you never considered, and to develop skills that go far beyond simple technique. Even if you never plan to write rhyming poetry, try your hand at sonnets, ballads, villanelles, and so forth. And when you’re experimenting, don’t be afraid to be bad. It is absolutely impossible to learn without making mistakes—including real whoppers!

What is the best advice (about writing) you have ever heard?

I used to think Pat and I were the first and only people to say, “Write what you don’t know.” Now I realize that saying has been kicking around for a while, and that it gets said a lot these days. It’s excellent advice. The world has got plenty of writers turning in upon themselves and their personal experiences. There is always a dire need for writers who reach outward, who test their own boundaries, whose creative work (as all creative work should be) is an act of discovery. Always be learning about something. Stretch your brain. Read the news and lots of nonfiction. Learn about the world of ideas. Meet people outside your circle. You just might never suffer from “writer’s block” ever again. There’s just too much wonderful stuff out there to think about and experience. Life is rich.

How many books do you read annually and what are you reading now? What is your favorite literary genre?

I will only say that I read as much as I possibly can, and I wish I could read a whole lot more. Most of the books I read are nonfiction. I am currently reading The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality by Walter Scheidel. Not that I ignore fiction and poetry by any means. My reading last year included Milton’s Paradise Lost, Toni Morrison’s God Bless the Child, Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind and the Willows, and an anthology of contemporary poetry called Legitimate Dangers. I’m eager to get back into re-reading Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, two towering and inexhaustible writers. I also read Shakespeare whenever I can; I’ve read everything in the canon at least two or three times. Oh, and the King James Bible.

What do you deem the most relevant about your writing? What is the most important to be remembered by readers?

One of the most common bits of advice a poet can get (or give) is “Find your own voice.” Instead, I look for other voices. I use my training as an actor and a playwright to try to create compelling and entertaining voices and characters. My poems tell stories. I also think that one of the key ingredients of a good poem is surprise. I try to bring surprise to my poems—surprise, thought, passion, and sometimes laughter.

Adrienne Rich once wrote, “A language is a map of our failures.” Poetry happens when words set us free from language. It is a liberation from unwitting collective prisons of thought and habit, for language binds us in more ways than we know. Fresh images, metaphors, and stories bring new vitality to our world of words and to our lives. I hope I contribute to that process of perpetual renewal.

I also agree with the late Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai that all poetry is political:

“This is because real poems deal with a human response to reality, and politics is part of reality, history in the making. Even if a poet writes about sitting in a glass house drinking tea, it reflects politics.”

In these days when the forces of oligarchy, bigotry, ignorance, privilege, and autocracy threaten to consume America and much of the world, poetry keeps us alive to the value of freedom, democracy, equality, and human decency. Every poem is an act of resistance.

What is your opinion about the publishing industry today and about the ways authors can best fit into the new trends?

Hunter S. Thompson once said, “When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro.” Writers are weird people and these are weird times. And you no longer have to be like the proverbial lonely teenager sitting by the proverbial phone, waiting for some Grand Pooh-Bah to deign to publish your work (mixaphorically speaking!). The possibilities for sharing and promulgating what you write are like nothing that’s ever been imagined in human history. The world hasn’t seen an age like this since Gutenberg. Throw yourself into it. Don’t miss a minute of it.

My father was a theater professor, director, playwright, and actor, so my very earliest memories are of attending play rehearsals. In a primal sort of way, this shaped how I’ve developed as a creative storyteller, whether I’m doing fiction, drama, or poetry. It also helped shape my growth as a person and how I view reality. Starting at the age of two, I watched actors slip in and out of character, oftentimes repeating the same actions and words over and over again, but in endless variations. These experiences left me with a lot of lifelong questions and obsessions. For example, what are the boundaries between life and performance, reality and imagination? How much of what we do every day and all the time is acting, and how much of it is really living—and is there really any difference? All my life I’ve observed those boundaries as constantly shifting. I’ve also come to see life itself as an act of creative storytelling.

My father was a theater professor, director, playwright, and actor, so my very earliest memories are of attending play rehearsals. In a primal sort of way, this shaped how I’ve developed as a creative storyteller, whether I’m doing fiction, drama, or poetry. It also helped shape my growth as a person and how I view reality. Starting at the age of two, I watched actors slip in and out of character, oftentimes repeating the same actions and words over and over again, but in endless variations. These experiences left me with a lot of lifelong questions and obsessions. For example, what are the boundaries between life and performance, reality and imagination? How much of what we do every day and all the time is acting, and how much of it is really living—and is there really any difference? All my life I’ve observed those boundaries as constantly shifting. I’ve also come to see life itself as an act of creative storytelling. Is writing the only form of artistic expression that you utilize, or is there more to your creativity than just writing?

Is writing the only form of artistic expression that you utilize, or is there more to your creativity than just writing?