Wim is grateful to editor Nolcha Fox for including five of his poems—including this one—in Chewers by Masticadores.

The Purloined X

A poem should not mean

But be.

—Archibald MacLeish

Tomorrow’s assignment

(Mr. Fritz told us,

lo, those many years ago),

is to find the poem’s meaning

and bring it to class,

in cuffs if it resists,

sedated if necessary.

To find its coordinates

(said Mr. Fritz)

make use of concordances—

one for Shakespeare

and one for King James—

and pluck out the heart

of the poem’s mystery

word by word

until you’ve got

the exact latitude and longitude

where the meaning lies in lurk.

And remember,

a poem can only have

one meaning,

like any other equation.

The meaning is x

so solve for x.

But I’d have none of that.

If there was one thing

I already knew for sure

even at that age,

it’s that meaning

can’t be come by honestly,

so I called the cops

who didn’t even bother

with a warrant.

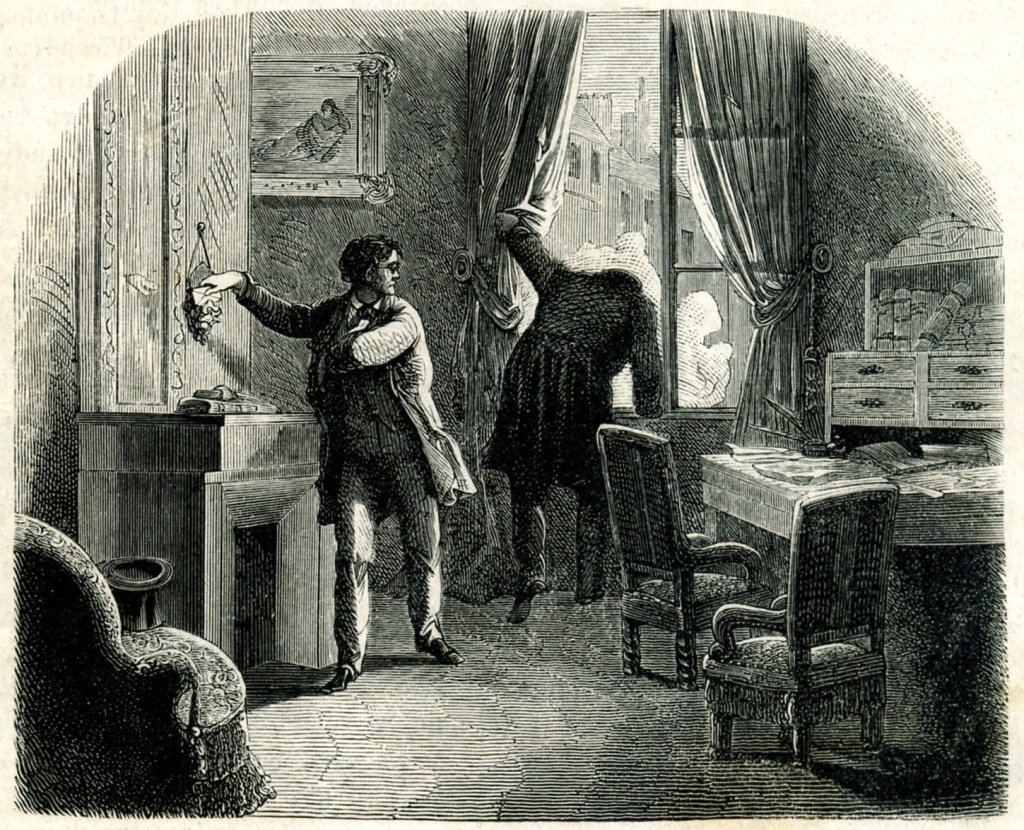

They smashed the door

and stormed right in

and turned the poem

upside down and inside out,

breaking all the furniture in sight—

but still no meaning.

Now I thought I was smarter

when I glimpsed

a folded piece of paper

tucked in a letter compartment

of the rolltop desk

right there in plain sight.

But when I seized it and unfolded it,

it was just a shopping list

for the day’s necessities—

a thing with feathers

a stately pleasure dome

a grain of sand

a wild flower

a red wheelbarrow

a wine dark sea

—just the usual stuff.

But when I went to consult

the little French detective

in his humble digs,

redolent of mildew and a meerschaum,

walls bedecked with Beardsley prints

and Toulouse-Lautrec posters,

he didn’t even have to rise from his divan

to figure it out.

Mon dieu, mon ami!

(he said, pouring each of us a glass of absinthe)

What silliness you talk!

Can you tell me what it is,

this thing you speak of,

this—this meaning?

I can tell you for certain

there is no such animal

as a meaning.

It is a make-believe creature

for the hazing of—

—how do you call them, you Américains?—

Boy Scouts, n’est-ce pas?

They put a tenderfoot alone

holding a bag by a hollow log

and tell him to stand there waiting

deep in the night

for the meaning

to show his little head,

and they watch

just out of reach of his earshot

snickering to each other,

those comrades of his,

while he keeps waiting there

like an idiot.

No, mon frère,

a meaning is a chimera,

a mere opinion,

and the poem holds opinions in contempt.

The poem is smart,

the poet its useful fool.

Now as for the poem in question—

never having read it

I am quite au fait with it,

for having read one poem,

I have read them all

and know wherein their secrets may be found.

You see, the x you sought

is very big,

the biggest thing there is,

the only thing there is,

and you were—comment tu le dis?—

getting warm

to think you saw it

right where anyone else could see it.

But it wasn’t in plain sight,

it was plain sight.

For a poem is not a thing that means,

it is a handless

springless clock

that tells only the moment,

only what is really there.

It is a thing

that conundrums the sense,

so to speak—

that blisses the heart

and fierces the brain

and verbs its breath into a world.

—Wim

BRAVO! WONDERFUL! CONGRATULATIONS!